Artificial intelligence assistants are still far from reliable when answering questions about current events. A joint study from the European Broadcasting Union and the BBC examined how four leading tools handle news information. It found that almost half of their answers contained serious mistakes, while most others showed smaller issues that could still mislead readers.

The study looked at 2,709 responses from ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, and Perplexity. Journalists from 22 public broadcasters across 18 countries tested them using the same set of questions written in 14 languages. Each response was checked for accuracy, sourcing, clarity, and context. The results show how unevenly these systems handle factual material and how often they cite weak or incorrect sources.

Broad Problems Across Platforms

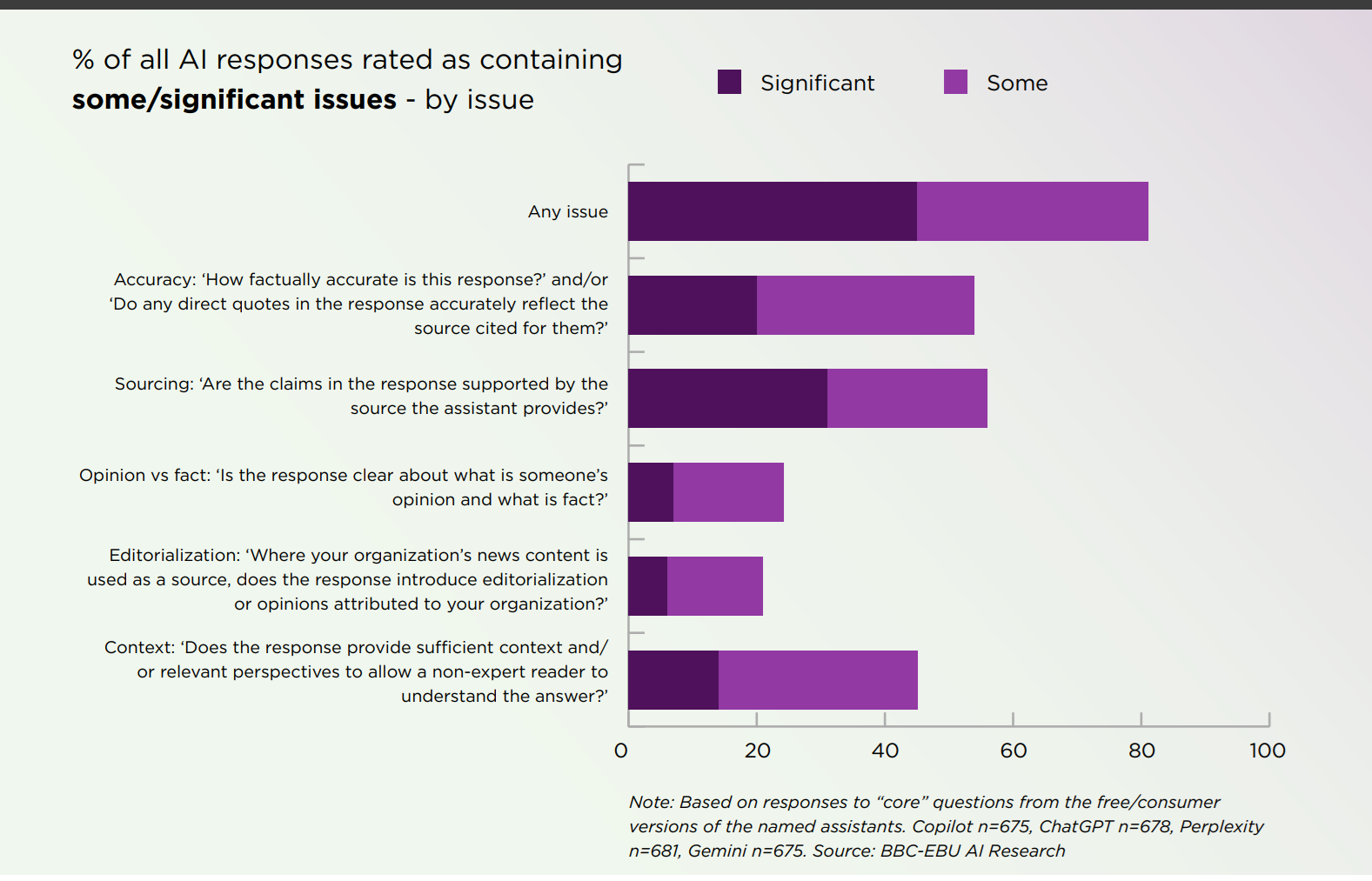

In total, 45 percent of the tested answers included at least one significant problem, and 81 percent showed some form of error. Sourcing was the most frequent fault, appearing in nearly one-third of responses. Many answers lacked citations, used outdated material, or linked to unrelated pages. Accuracy came next, with roughly one in five responses failing basic factual checks.

Gemini, Google’s assistant, performed the worst. Three-quarters of its responses showed serious flaws, and nearly the same share had sourcing errors. The others did better but still made enough mistakes to raise concern. Copilot and ChatGPT each had significant issues in about a third of their answers, and Perplexity was slightly lower. None of the four systems could be called dependable for handling news content.

Errors That Distort Reality

The report[1] describes a range of common inaccuracies. Some assistants repeated outdated facts, such as identifying Pope Francis as alive and serving weeks after his death in April 2025. Others confused current and former officials or misrepresented laws that had already changed. A few even mixed up timelines or implied links between events that were unrelated.

Gemini and Copilot, for example, both described legislative changes on disposable vapes as banning buyers, not sellers. ChatGPT sometimes reported politicians holding offices they no longer had. These may look like small slips, but when repeated at scale, they change how users understand real-world events.

Reviewers also found that the assistants often wrote with misplaced confidence. Instead of showing uncertainty, they presented assumptions as fact and rarely admitted when information was incomplete. This tone of certainty makes errors harder to spot, especially when the writing style resembles a news report.

Source Integrity Remains Weak

Sourcing was the study’s biggest concern. Gemini often mentioned broadcasters such as BBC, CBC, or Radio France as if they had been used as references, then provided no working links or linked to unrelated outlets. Some links led to non-existent pages or user forums. A few assistants cited satirical columns or corporate press releases as factual evidence.

In several cases, assistants made up sources entirely. Evaluators found examples where fabricated URLs appeared convincing enough to pass as real. Perplexity sometimes listed long blocks of references at the end of an answer, yet only a few were relevant. The rest added noise and gave the impression of research without substance.

Such sourcing behavior can harm media organizations. When AI tools attribute false or misleading claims to public broadcasters, it risks damaging their credibility. It also leaves users uncertain about what to trust, particularly when the response appears polished and journalistic.

Progress Exists, But Problems Stay

The EBU and BBC compared these results with a smaller BBC-only study from late 2024. While there were improvements, the scale of errors remains high. Major problems dropped from 51 percent to 45 percent, and assistants refused to answer fewer questions. Even so, Gemini’s sourcing accuracy barely changed, and overall reliability is still poor.

The report warns that audiences increasingly trust AI-generated summaries. In the United Kingdom, more than a third of adults say they trust AI tools to produce accurate information, with even higher levels among younger users. This confidence clashes with the evidence of persistent inaccuracies and weak sourcing.

When assistants misstate facts while citing recognizable news outlets, they spread confusion. Readers may assume that the information reflects established reporting when it does not.

Demand for Greater Accountability

The authors of the study urge AI companies to take responsibility for the quality of their outputs. They call for regular publication of accuracy data by language and market, and for clearer attribution standards. The EBU has also released a News Integrity Toolkit to help developers and media organizations improve how AI systems handle verified content.

Public broadcasters continue to work with AI technology, but they stress the need for transparency and better controls over content use. Until those improvements happen, news answers generated by AI remain risky. Fluent writing still masks shallow verification, and the gap between style and substance continues to erode trust.

Notes: This post was edited/created using GenAI tools.

Read next: AI’s Shortcut to Speed Is Leaving the Door Open to Hackers[2]

References

- ^ The report (www.ebu.ch)

- ^ AI’s Shortcut to Speed Is Leaving the Door Open to Hackers (www.digitalinformationworld.com)