- Aiode has launched its desktop AI music platform for artists and producers

- The company emphasizes the platform’s ethical AI training

- Aiode will pay the real musicians whose styles were modeled

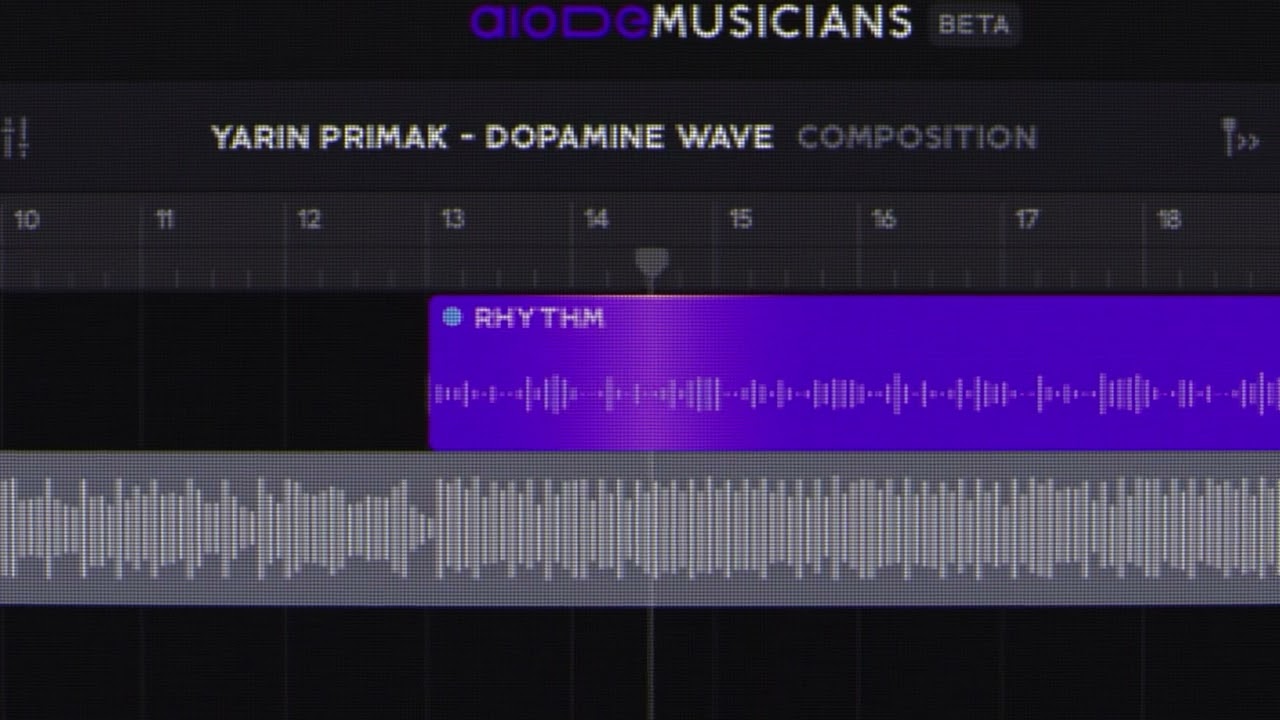

Music tech developer Aiode is humming its first tune with the official launch of its desktop AI music platform. The toolkit combines music production and editing software employing AI, but with an eye toward musicians looking for more precise control over how AI influences their songs.

Aiode uses what it calls virtual musicians to make its platform work. The virtual musicians replace generic music fill-ins with AI models based on actual performers. These synthetic session musicians adapt to the style you want, but they also bring their own sensibility, much like actual collaborators, albeit robotic ones whose programming can be adjusted.

Aiode spent a year undergoing testing, but users can now regenerate or refine specific sections of a song, like the chorus or a solo, without reworking the rest of the composition. Aiode pointed to this targeted regeneration as one of the most liked features from the private tests. This serves as a remedy for the recurring complaint that AI music tools don’t allow for much finesse in how songs are sculpted.

“We built Aiode for the way music is truly created,” said Idan Dobrecki, co-founder and CEO of Aiode, in a statement. “Creators don’t need gimmicks or shortcuts – they need tools that respect their intent, keep them in control, and help them move faster. That’s exactly what this launch delivers.”

Aiode’s musical ethics

Perhaps more than features, Aiode leans heavily on its ethical narrative. The company says its model training is transparent, that real musicians whose styles were modeled will receive compensation, and that creators always retain control over output and rights. In a space where copyright, attribution, and exploitation are perennial flashpoints, that positioning could attract cautious artists who otherwise avoid AI tools.

By comparison to AI music providers like Suno or Udio, Aiode might take more work before a song is finished. The aim is more about reshaping ideas than taking an initial notion and getting most of the way to a ready-to-play song. And while Suno and Udio operate mostly in cloud-based generation, Aiode’s desktop focus gives it room for lower latency.

With Suno, you can type a prompt, wait a minute, and get a song. With Aiode, you bring in more of a filled-in outline, call in a virtual pianist and drummer, get them to generate a second-verse variant, tweak the fills, and then export the result. That said, the release of Suno Studio[2] somewhat changes matters as Suno’s new platform comes with plenty of robust editing tools. But the overall dynamic and approach to crafting songs is still very different from Aiode.

Not that Aiode won’t have its own problems, both technical and creative. Phrasing mismatches, harmonic clashes, and awkward transitions are inevitable with enough use. Plus, the quality of its virtual musicians depends on the training data, which may be less robust because of the ethical approach. And that same approach lends itself to complications at scale, with questions of misuse, compensation, and attribution likely to crop up.

As hundreds of thousands of AI‑generated tracks flood streaming services and complaints about fraud and copyright pop up more often, Aiode foregrounding attribution and rights may make it the most appealing option in the long run. Building an ecosystem where musicians are not hidden under AI, but incorporated (and paid), may be a competitive advantage and not just a marketing slogan.