As each year drew to an end, I came to dread the email from the care home where my uncle stayed. It would be headed ‘Fee Review’, and the fee only ever went in one direction – up.

My uncle Richard had built up a healthy savings pot and owned his house mortgage-free when he was struck by a catastrophic stroke 30 years ago, while in his late 50s.

I can’t say exactly how much he’d saved because it was my father who initially took over his affairs, being appointed his deputy by the Court of Protection.

Now that duty has devolved to me, and I can say exactly where the money is going – into the bottomless pit known as care home fees.

For many years he lived in a home called Wellcross Grange in Horsham, West Sussex. In 2020 his monthly standing order was £3,410.

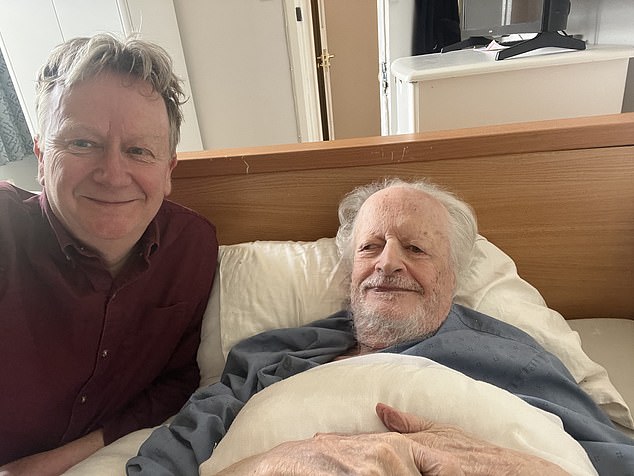

Stroke victim: Richard in his new care home with his nephew Andrew after the fees at his old home soared to £7,500 a month

The actual fees charged by the home were rather higher but were partly offset by funded nursing care, which varied between £700 and £800 monthly.

This is an NHS payment that he qualified for because he had been assessed as needing care from a registered nurse. The monthly fees did not include extras such as hairdressing, foot care and toiletries.

In November 2020, the annual fee review pushed the monthly standing order to £4,869. DSL Care Ltd, the company that runs the home, blamed staff costs and Covid-19.

It said staff costs were also responsible for the subsequent three annual rises to £5,313, then £6,047 and £6,541.29.

The final straw was the fee review effective from January 1 this year – although it wasn’t so much of a straw as another giant bale crashing down on my uncle’s savings.

The monthly charge was rising to £7,500. Within five years, his fees had more than doubled.

The company partly blamed the Government’s increase in employers’ National Insurance payments.

‘The review also reflects, where applicable, changes in individual resident care needs,’ it emailed.

I asked the home to be more specific about my uncle’s changing care needs, wanting to know how it could justify a 15 per cent fee increase when inflation[1] was running at 3.5 per cent.

It cited ‘an increase in the amount of care and supervision needs, mainly due to medication management and falls risk management.’

If his care needs were really growing so much, then it was possible that he would qualify for NHS Continuing Healthcare funding. Recipients of this receive care for free.

But when I asked Wellcross Grange if my uncle would qualify, the care manager replied: ‘I believe there is not enough complex nursing care evidence to support this.’

So, my uncle’s needs were not severe enough for Continuing Healthcare funding but warranted the latest fees hike.

Half of the money to pay these fees comes from his state pension, a private pension and state funding such as Disability Living Allowance, and the other half from his diminishing savings.

If the fees continue to rise at the same rate every five years, then by 2030 they’ll have reached £16,500 a month, or almost £200,000 a year. How many people can afford that?

It was little compensation knowing that my uncle is not alone in facing this predicament.

Of the 400,000 or so people in the UK living in residential care and nursing homes, only around half get local authority or NHS financial support, with the rest paying for their care privately.

The monthly average cost of residential care is £5,164, or £6,180 monthly for nursing care, according to industry website carehome.co.uk.

‘The extraordinary rises in some care home fees is very worrying. Most people who need social care have to pay for some or all of it themselves,’ says Caroline Abrahams, charity director at Age UK.

‘The ongoing cost-of-living crisis means they are facing even higher bills, draining their savings faster than ever before.

‘This isn’t the fault of care homes because most of their costs have risen, including their wage bills, meaning they generally have no choice but to pass these increases on.

‘The way social care works at the moment means that it is the consumer who is hit hardest when prices are rising quickly.

Meanwhile, all the evidence is that the chances of obtaining state-funded care are not getting any better and, in fact, are probably getting worse.’

Heledd Wyn, director at The Association of Lifetime Lawyers, echoes that view. ‘The rising cost of care home fees is a source of great anxiety for many families,’ she says.

She adds: ‘There are several reasons behind the increases, including higher staffing costs, rising insurance premiums and a growing gap between what local authorities can afford and what private individuals are charged.

‘With many care homes operating on a for-profit basis, private residents often end up shouldering more of the financial burden, especially as social care remains means-tested in England.’

In England, you might qualify for funding assistance from your local authority when your capital falls below £23,250 (the amount is higher in Wales and Scotland). By my calculation, my uncle will reach this point in seven years, possibly sooner, depending on future fee increases.

After discussions with my family, we reluctantly decided that he must be moved to a more affordable home, and found one that would charge £1,500 less each month.

I’m pleased to say he is now in a new home and is very content.

Ian Campbell Lyle, a director of DSL Care, says: ‘While inflation and government legislation have certainly impacted care providers in general, it is the increased care needs that have been the main factor in the price changes.

‘We understand that there may be more affordable options, but we believe that the high quality of care at our home remains a key differentiator.

‘We are saddened that he was unable to remain in our care and wish you luck with his new placement.’

The move has bought my uncle an extra couple of years of care before his savings run out. Then we’ll be at the mercy of the local authority funding.

It is not an enticing prospect, as residents are being forced out of care homes when their savings run out, according to Nadra Ahmed, co-chair of the National Care Association, which represents small and medium-sized care firms.

Tuned in: Richard in his younger days. He was struck by a catastrophic stroke 30 years ago, while in his late 50s

Private funders pay around £1,300 a week on average, whereas local authorities will pay only around £700.

Unless the family of the resident can make up the difference, or the care home accepts the lower fee, then the resident is likely to be moved to cheaper accommodation.

‘Local authorities used to top up the fees but they no longer do that,’ Nadra says. ‘It’s bad enough having to leave your home for a care setting without having to move again.

‘You get used to staff and the service, and friendships develop. It can be heartbreaking when someone has to leave.’

You can choose to complain about care home fees to the Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman.

It recently upheld a complaint from a son who said a care home had increased his mother’s charges without changing her contract and without any assessed changes to her needs.

The provider, Moors Park (Bishopsteignton) Ltd in Teignmouth, Devon, refused to apologise or issue a refund to the woman and other affected residents. It was referred to the regulator, the Care Quality Commission, which has cancelled the provider’s registration.

‘When care providers believe clients’ needs have increased, and it is costing more to meet those needs, they first need to assess what those needs are,’ said the Ombudsman, Amerdeep Somal.

‘Any changes to their contracts need to be transparent, justifiable and based on these assessed needs.

In this case, the provider has not provided me with any evidence to justify the increase in fees it has charged, and in fact increased the amount the mother paid before carrying out any assessment of need.’

What I wish I’d known…

There are ways to keep fees in check and make life easier should you need care. Jane Finnerty, a director of the Society of Later Life Advisers (SOLLA), suggests the following…

- Get advice as soon as you can: Even if you’re in your 40s or 50s, it’s sensible to get help with long-term financial planning.

‘There might be more options available to pay for care earlier in someone’s care journey,’ says Jane. Early planning can also prepare for the possibility of sudden unexpected illness.

A SOLLA-accredited adviser (societyoflaterlifeadvisers.co.uk) can look at ways to pay for care, as well as ensuring you are claiming benefits such as Attendance Allowance, which is paid to those with a disability or health condition that is severe enough for them to need help with their care.

The advisers should also cover retirement planning, tax and estate planning, and property options such as equity release.

- Have a Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) registered: Get an LPA for your finances and health and welfare as soon as you can. The attorney will make decisions for you if you become unable to make them yourself.

You can appoint a relative, friend or professional such as a solicitor to be your attorney by registering their details with the Office of the Public Guardian. The forms can be downloaded from gov.uk/power-of-attorney

- Look into financial products: There are products that can provide a guaranteed monthly payment to help cover fees. These are for people who need long-term care and want to reduce the risk of exhausting all their savings.

Firms such as Legal & General offer an ‘immediate needs annuity’ which provides a monthly payment for life to help with care fees in exchange for a single lump-sum payment. However, it might not be possible to recoup any money from the initial payment if the care is no longer needed.

Estimating costs of an annuity plan is difficult because they are tailored to the individual and consider factors such as age, life expectancy and the income needed. Shop around, because providers’ quotes can vary greatly.

- Talk to your local authority: It might offer support even if you are self-funding your care. The first step is to ask your council to carry out an assessment of your care needs for free. If you need care, the next step will be a means test to calculate how much, if anything, the council will contribute.

You may be limited to homes offered by the council, and only be able to move to somewhere more expensive if you can find a relative or friend to top up the fees.

- Consider NHS Continuing Healthcare: For someone whose care is focused on medical needs rather than social care, talk to the care home about NHS Continuing Healthcare (CHC) funding.

CHC is aimed at people with long-term complex health conditions and requires assessment by a team of health and social care professionals.

- Use a specialist solicitor: Get someone from the Association of Lifetime Lawyers (lifetime lawyers.org.uk) to look over the care home contract. Jane says: ‘You’d do this if you were buying a house, and if you are paying for care over several years the outlay could be substantial.’

The contract should cover what fees are fixed and what are subject to change, and what additional costs there might be for services such as laundry.

It should also be specific about the type of personal care that will be provided in areas such as washing, dressing and eating, and the type of medical care that is included.

Also check clauses covering the type of accommodation – for instance, whether the room is ensuite – and whether there are any restrictions on visiting rights.

The Association can also help appeal funding decisions made by your local authority or the NHS.

moneymail@dailymail.co.uk