Isabelle Brourman in front of the New York courthouse where she sketched Donald Trump’s hush-money trial. Ted Shaffrey/AP

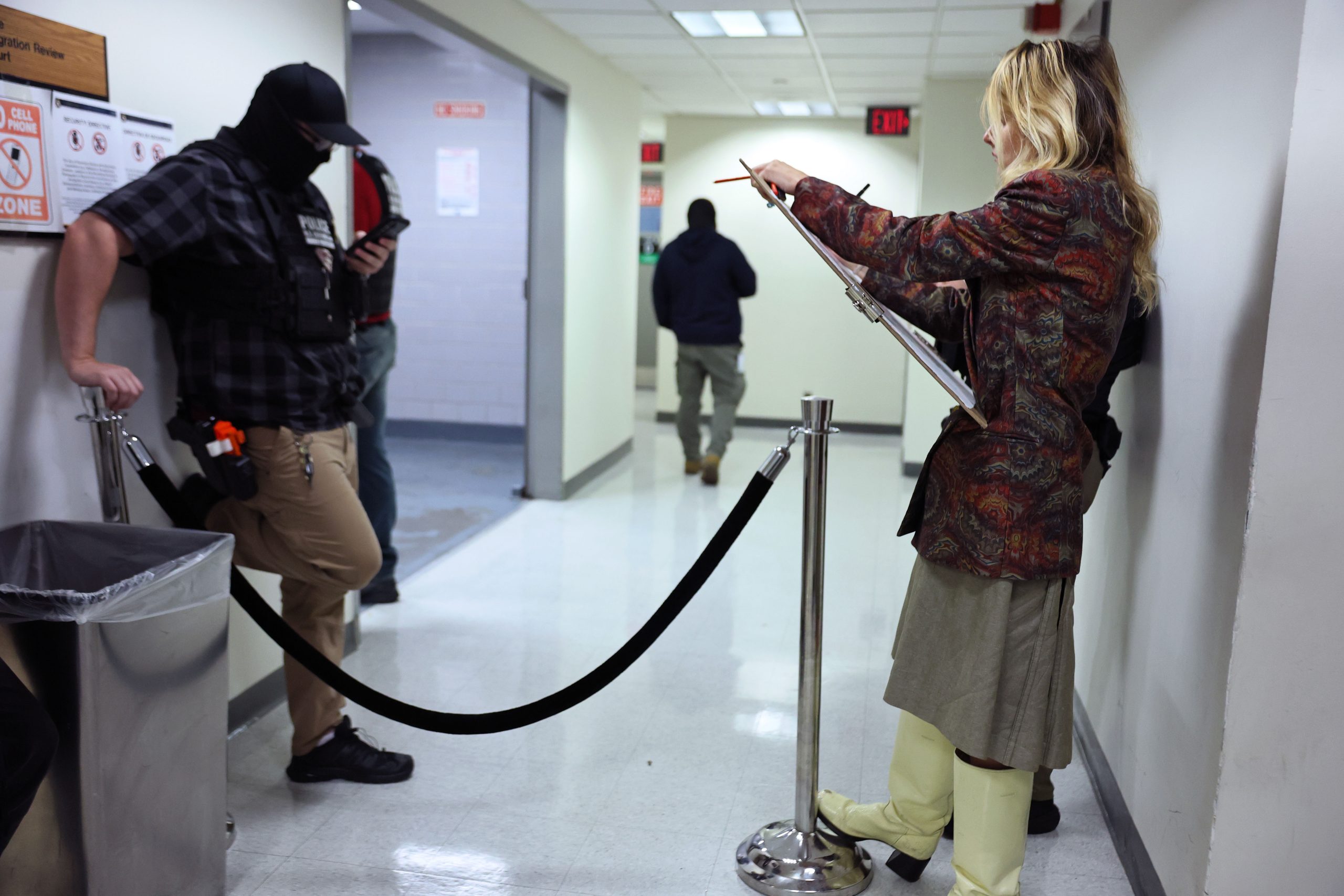

In June, Isabelle Brourman took a sketch board and her press pass to immigration court at 26 Federal Plaza in New York City. She’d heard that US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers were arresting people after their hearings, and she wanted to document it. Court security wouldn’t let her inside.

Brourman, a 32-year-old mixed-media artist, tried to explain who she was. She’d built a reputation by then—first at the Johnny Depp v. Amber Heard defamation trial in Virginia, and then at Donald Trump’s hush-money trial in New York, working alongside court illustrators who sketch for news outlets when photographers aren’t allowed inside.

Unlike her peers, Brourman doesn’t render her subjects realistically: Her style, which she’s described as “Tasmanian-devil glamour,” includes swirling lines, bold colors, and snippets of dialogue that capture not just the content of proceedings, but the emotions. So unusual was her work that she grabbed headlines herself, earning profiles in the New York Times and even catching the president’s eye: After his trial, he let her paint him at Mar-a-Lago.

But at 26 Federal Plaza, security remained unimpressed. “They were concerned I was a protester,” she told me, and they turned her away. Undeterred, Brourman eventually found a way inside and set to work convincing the immigration judges to let her stay. I recently caught up with her after a long day at court to ask what she’d been seeing—and what it was like meeting Trump on his turf.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How does the environment in immigration court differ from scenes you’ve documented before?

Oh, my. The other trials surrounded very high-profile public figures, and that dictates what kind of spectacle it is. The spectacle in 26 Federal Plaza has more to do with the ICE agents. There is an anonymity to the respondents that I’m documenting, and so you’re covering almost like ideas and bodies of people and forces, rather than specific characters.

I’ve been lucky enough to document a lot of warmth in the courtroom as people wait with their families to speak to the judge: kids passed out across both of their parents’ laps. Sons who are going up to speak to the clerk because their mom doesn’t speak English. The warmth amplifies the grief that can follow when somebody is taken.

Tell us about your first day at 26 Federal Plaza.

I showed up with my board and paper, and my press credential, and I was not allowed into the building. I showed them my work, articles. I explained I have the right to go in, just like anybody else in the public space. And it was a no. So I came back the next Monday and just put my board in a case and got through, and then spent a lot of time explaining to clerks and administrators who were trying to keep up the procedures—no photographers allowed in the courtrooms—that that was my job, specifically, as a courtroom artist, to supplement photography. They’d never had a courtroom artist in the building.

After that, I waited on the communications person, who sent an email to the judges and said, “You can decide whether to have her in there.” So I’ve been going around courtroom to courtroom, and then following some of these respondents into the hall to document their fate there.

In the hallways, have you witnessed any arrests by ICE?

Oh, tons.

What did you observe?

There are the sounds, like from within the courtroom: The doors are often open, so we can hear it beginning—the hallways are small, and there are the agents, the photographers, and then the lawyers who show up and try to tell immigrants their rights, chasing them down the hall.

It’s haunting, I think, to respondents who are still waiting to talk to the judge. There was one mother who was like, “Too much, too much.” And these kids who are sitting at the respondents’ tables, tiny in a big chair, and you see them turn their head and peek at that, and then crawl under the table, because they’re playing, because they don’t understand.

I was in one courtroom, speaking with the judge, and we heard a noise from the wall with the courtroom next door. And the clerk jolted and was like, “Did you hear that? I’ll go lock the door. Something’s happening.” And the judge said, “No, I want to see.” And so I exited, and there was a man from Morocco, couldn’t have been more than 25, being taken by ICE agents.

He was brought into the stairwell to be cuffed, and a group of photographers and myself, we listened to him cry and plead. There was nothing anyone could do except witness it. After that, I spoke to the court observer, because it was just so devastating, I felt the need to know more. What the sound I heard was: He was frozen, because the agents were at the threshold of the door and there was no one else left in the gallery, so it was him they were waiting for. One of the head agents had his hand wrapped around the door frame, like an inside-outside type situation, and they just stared at each other. And the judge said, “It looks like there’s a situation here. I’m going to take a break.”

The judge went into the chambers, and the clerk said something along the lines of, “We can’t do this all day.” And then the agents stepped in. He tried to run from them and jumped over the railing and into the clerk’s area, and tried to get out the chamber door, but that was locked. Then the ICE agents pinned him, and he was brought out, and that’s where I saw him.

How awful. Is there a mix of responses from judges to these arrests?

There’s a dramatic range, from judges that are a bit emotive to judges that are sort of—it’s as though there’s nothing happening. They’re resigned, or stone faced and systematic, and they’ve categorized it into a different system of government in the hall. I mean, I’ve heard judges say to respondents who were concerned—I have the quote here—“If there’s anybody out there, they don’t work for me. I wish you the best. We are adjourned.”

There was another judge who said, “Everything that happens inside this courtroom is one thing, and everything that happens in that hallway, it’s a public space, and there’s nothing I can do about it. They’re allowed to be there.”

What other arrests have really stood out to you?

I was in the waiting room drawing, and a man came out of the courtroom and one of the agents said, “Okay, you’re coming with me.” The man walked toward his partner, who was standing with the stroller, to hand her papers, and then he went to pick up his baby. And like seven agents leapt to the stroller and were all holding onto the stroller, surrounding the stroller, and wouldn’t let go.

It was total commotion. The baby was inside in a diaper and a Mickey Mouse shirt, and could have gotten really hurt. The mother was crying and frantic. They turned the man against the wall and had his neck pressed against the thermostat. The man was screaming, I’m not a criminal, I’m not a criminal, America is supposed to be free, something like that.

Talk a bit about your interactions with the ICE personnel.

I’ve sat in the halls and drawn officers. The real tension is between the officers and the photographers—a lens might hit the head of an officer, and they’ll say, “Did that just hit me in the fucking head? Did you just hit me in the fucking head?”

In the moment of detainment, it’s intense. And then after, when everyone’s lingering, there’s a casualness; there’s often so much time passing that there’s a lightheartedness among the agents, who are bonding behind their uniforms, and you only see their eyes. I wrote down that at one point I looked up and saw all these eyes, like panting, and there was just laughter.

The officers’ interactions with me have been pretty much positive. They’re interested in seeing themselves in the drawings. This happens all the time. I’m always surprised, like I’ve had people who are going on the witness stand, who I would think are having a really shitty day, and their secretaries have come up to me and asked for my information because they want to buy the work after. I’ve had officers look over and ask where they are, and then show their friends, fellow officers. They like the work. They think it’s cool. I had an officer see me drawing and then go into the thinker pose. It’s uncanny, you know. But I’m also used to the work being a source of disarmament.

Have you shown your work to the immigrants and their families?

Yeah. The kids love it. A lot of times, kids will come over and I’ll hand them a marker and let them draw, even on the work, because that just adds to it. There was a boy, Matthew, who was across from me with his mother and his two brothers, so I gave him a colored pencil. And I asked what he wanted to be when he grows up, and he held up his hands like a binocular. And then he finished the drawing, and I looked at it, and it was this boy holding binoculars. And I went into my bag, because court artists are allowed to have binoculars, and pulled out a pair, and he thought I was a magician or something. I handed them to him, and then drew him with his big smile and his binoculars. I gave them to him.

After, sometime in the afternoon, they were coming out of the waiting room, and I saw his mother talking in Spanish, like, Por qué? Por qué? His father had been detained. She fell to her knees. And Matthew was standing, watching the photographers, the agents, and then turning to his mom, and he was holding the binoculars.

How would you describe your style? How does it differ from the work of other court illustrators who work for the press?

The style is organized chaos, improvisational. I had a lot of feedback from the Trump trial about the energy and emotional tension, things that a lot of people covering those trials don’t have the luxury of picking up on, because they’re paying attention to the minutia of the proceedings.

What I like to do is collage all the elements inside and outside the courtroom: If there’s an interesting pattern of officers on Broadway outside at a protest, marching from the police vehicles, I have that along one side of the elevator that Matthew’s family was in.

You’ve said that your work in immigration court fits within a broader project you call “The Aftermath.”

That’s what I’m terming everything after the inauguration. It’s divided into images from the courtroom, on the road, and portraiture—that started at Mar-a-Lago when Trump was a former president, a presidential candidate. He had just been shot in the ear, had just been convicted on 34 counts. And also, weirdly, I had seen him every day for a year at the trial, so he kind of felt like a colleague?

I had pitched a portrait and an interview with Olivia Nuzzi for New York Magazine to his press people. He didn’t say no; he just said he doesn’t want the art to be screwy. And I was like, no, this is going to be an oil painting. So I got an easel, had a canvas stretched, and this was like a royal court situation. Those paintings—I haven’t spoken about them yet. It was not just a portrait of Donald Trump. It was a portrait of America, and the feeling, and what I had seen all the way up to that point, and also all the anticipation and the wondering of what was going to happen next. So, I left the bottom of the portrait empty, blank.

Most recently, I went with my creative partner, Jeannette Berlin, to Tucker Carlson’s studio in Maine, and I did one panel there. I painted the inauguration as well—I documented it in the lobby of my hotel, people who were there to clank champagne glasses and chant USA. Then I painted the military ball, in the press risers with Fox News—Hannity’s set was one riser below mine.

The people who attended were members of the military and their families or partners, and so I had [Defense Secretary Pete] Hegseth an inch from my canvas. (I had gone to DC to do the confirmation hearings, and the press gallery revoked my pass and said there was a rule against art. I tried to tell them that a lot of people get information from these drawings, but it was a no-go.)

I also did a portrait of Luigi Mangione after court one day—he’s an interesting perceived threat to a lot of the people that I’ve drawn in the political landscape, but also he has a lot of power with the public.

What was it like doing the portrait of Trump, being close to him for that long?

There’s a bundle of adrenaline when you’re painting someone in front of them, especially him, somebody who’s very tuned into how he is represented in images. It was unprecedented and bizarre, and there was a level of humor and also terror—we were talking about something so somber [after he’d been shot]. When he came in initially, he pointed to the canvas, and said, “The reason I’m doing this is because I’m competitive. She wouldn’t do this.”

Referring to Kamala Harris.

That was information for me. And also, because he said that, I tried to paint her too. I tried every way I could think of—I tried to get there on Election Night, through a different magazine, they reached out and asked if the vice president would sit for a portrait, and I ended up getting a very nice, strange-now email from one of her people the day of the election, saying, you know, I’m paraphrasing here, but let’s talk about the inauguration.

Did Trump like your depiction of him?

Yeah. He said it was “different.” I went back and did a follow-up—I told him I wanted to get the ear right, so could I come around with my board that you usually see in the courtroom, and sketch a study of the ear, which he allowed, and so I was like a millimeter away from the ear. Just looking at the—he called it a “rail track,” because it was like a little dent in the outer perimeter. He took me through it, and I was like, “It’s so crazy how close your ear is to your brain and how much damage there could have been, and how little damage there is.” He agreed. And he had meetings afterward, and he didn’t say to go—like, we weren’t dismissed. So I continued to paint.

“He asked me what my concept was, and I told him I’m gunning for the presidential portrait.”

I had brought him at that point a very worked-out painting, and he took a look and was like, “I look really serious. I’m not sad, am I? Like, I’m a happy guy.” And that, to me, is great information, live information that I used in the portrait. So I gave him a smile, and then to create the feeling that existed on that day in the country, I decided to make his eyes black and the back of him, which represented his trail forward, white and blank, because we didn’t know, but I later filled it in. So his eyes were black [laughs] when I brought him the painting. I was pretty nervous. And he actually liked it, and let us stay.

He conducted all his meetings in the living room where I was across from him, and people started to fill that space. He was perfectly nice to me—he registered that it was an interesting mise-en-scène thing for the day, like he’d just decided he was going to utilize it in the meeting. And so [former Rep.] Matt Gaetz came in, and Stephen Miller came in, and Trump is complimenting my work and not really giving anyone else compliments. And so, at a certain point, everybody’s one by one coming and looking at the work and puzzling over it. And then he was like, “Okay, meeting’s over,” and he came by and looked at the painting and said, “You know, it’s different.”

It’s always really freaking scary, like you don’t know how the painting is going to live—it’s connected to a live wire, to somebody who’s so unpredictable and has a tendency to engage with people who create things about him, or cover things. I don’t think he had ever, even for the first presidential portrait—he didn’t sit for that portrait. So this was an opportunity for me to feel. Which is what I’ve been doing with the court work and why I like it. It feels fresh.

After he was elected, I reached out about painting at the White House, which he’s agreed to do. We don’t have a set date, but he asked me what my concept was, and I told him I’m gunning for the presidential portrait.

Have you considered sharing your immigration court illustrations with him, given that you’re documenting how his policies are affecting families like Matthew’s—their grief?

I’m not hiding it. I’m not walking on eggshells. I’m not going to not cover that because of my coverage of Trump. In fact, I am going to cover it, because that’s directly connected to him, and it’s important that I be there and document it. I would show it to him, but nothing is going to stop me from creating.

So many people have tried to pin me down on one side or another side, and I’ve gotten criticism for just paying attention to him—and that is an issue, a big issue, that basically narrows our understanding of the story. What I’m doing as an artist is exercising my freedom to cover everything and to pay attention to what I feel needs to be paid attention to, and I work my damnedest to get into the spaces that I think should be documented. It’s less about him and more about the country, about understanding where we are.