Archaeologists may have found evidence of an advanced civilization wiped out by a global flood 20,000 years ago, a discovery that could rewrite human history.

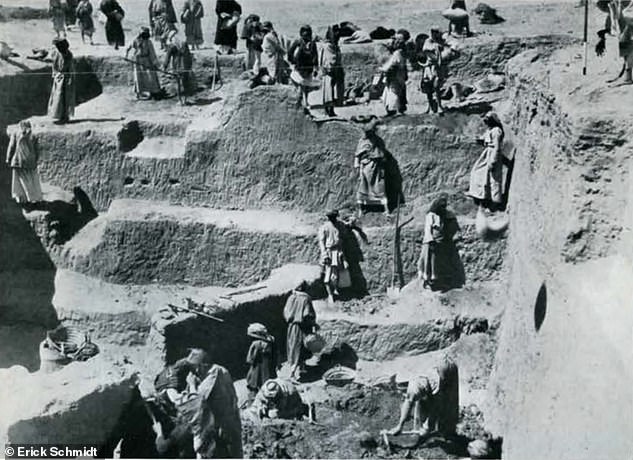

Excavations at Tell Fara in Iraq during the 1930s revealed settlements dating back more than 5,000 years, in a period known for the emergence of cuneiform writing, centralized rule and complex urban organization.

Tell Fara has long been considered a key Sumerian city-state, offering vital clues about early civilization, trade networks and administrative practices.

But beneath the settlements, researchers discovered a thick layer of yellow clay and sand – an ‘inundation layer’ – indicating a massive flood that predates the known settlements.

Such deposits typically settle on already-inhabited ground, raising the possibility that an even older civilization may have been buried and erased by cataclysmic waters.

Similar flood deposits have been documented at Ur and Kish in Mesopotamia, Harappa in the Indus Valley, and even at ancient Nile settlements in Egypt.

The recurrence of these catastrophic layers across multiple continents suggests entire communities worldwide may have been wiped out by sudden floods, leaving only myths and fragmentary archaeological traces.

Independent researcher Matt LaCroix told the Daily Mail that geological records indicate a global disaster roughly 20,000 years ago. ‘Nothing in the last 11,000 years even comes close to explaining it,’ he said.

Excavations at Tell Fara in Iraq during the 1930s revealed settlements dating back more than 5,000 years, in a period known for the emergence of cuneiform writing, centralized rule and complex urban organization

Pictured is a cuneiform tablet. This one was is around 4,500 years old and includes information about Mesopotamia from between 2500 BC and 100 AD

He added that abrupt climate events could have triggered floods powerful enough to inspire myths found across cultures.

‘A global catastrophe of this magnitude could have destroyed entire communities, leaving only fragments of culture and memory behind.’

Ice core records reveal abrupt climate swings, including the Younger Dryas cooling around 12,800 years ago, which some researchers believe may have triggered catastrophic floods.

But most scientists argue that while the Younger Dryas caused major regional climate shifts, there is no evidence it produced a single global flood or wiped out an advanced civilization, making the theory widely viewed as fringe.

Critics note that most humans during the Upper Paleolithic were small, nomadic hunter-gatherer groups, leaving little direct evidence for complex societies at this time.

While mainstream scientists dismiss a global flood at this period, LaCroix contended that the evidence points to an earlier, far larger catastrophe.

He dated the cataclysm to roughly 20,000 years ago, not through direct archaeological finds, but by correlating geological records with global catastrophic markers.

To do this, he examined ice cores, tree rings, volcanic debris and geomagnetic excursions to pinpoint periods of extreme worldwide disruption, then cross-referenced those with ancient flood myths and astronomical alignments.

Artifacts found beneath the inundation layers, including proto-cuneiform tablets, polychrome jars and Fara II-style bowls, point to a far more sophisticated society than previously recognized.

Archaeologists who uncovered the site said the ancient people may have been given a warning about the flood, as they only found a small number of skeletons (pictured)

He maintained that these natural records reflect the same event described in ancient flood traditions.

In his view, disasters 12,000 to 14,500 years ago, such as the Younger Dryas, were significant but too regional in scale to match the widespread devastation described in ancient accounts.

By ruling out those later events and combining multiple strands of indirect evidence, he concluded that only a much earlier catastrophe, possibly more than 20,000 years ago, fits both the geological record and the cultural memory preserved in myths.

If correct, this timeline would push the origins of civilization back by at least 8,000 years, challenging the standard view that places the first cities around 5,000 to 6,000 years ago.

Ancient Sumerian texts describe Šuruppak as a ‘pre-diluvial city,’ home to Ziusudra, the Sumerian equivalent of Noah.

LaCroix suggested the alignment of flood deposits at Tell Fara, Ur, and Kish with these legends is ‘not merely a coincidence, it points to a shared memory of real catastrophic events.’

Independent researchers analyzed images from the site, which showed intricate seals from a forgotten civilization they believe could be around 20,000 years od

Evidence from the Upper Paleolithic period shows humans 20,000 years ago lived as nomadic hunter-gatherers, forming small, interconnected groups that relied on stone, bone, and wood tools.

Yet the artifacts found beneath the inundation layers, including proto-cuneiform tablets, polychrome jars and Fara II-style bowls, pointed to a far more sophisticated society than previously recognized.

Sharp differences between artifacts above and below the flood deposits suggest an abrupt cultural break, as if an entire civilization had been erased and later rebuilt.

Lead archaeologist Erick Schmidt, from the Penn Museum, noted that excavations revealed settlement layers up to 6ft deep.

He wrote: ‘One of our most interesting problems is now, has the rising of the waters completely destroyed towns, men and beasts?’

Schmidt added that if remains of humans or animals are never found, it might indicate that populations were warned and fled before the catastrophe.

‘Has the culture, existing prior to this event, been completely erased at this locality, or, speaking archaeologically, is there an absolute culture break expressed by the total difference between the remains below and above the alluvial layer?’ he wrote.

LaCroix and others have proposed that this lost culture could have been part of a global network, leaving behind only myths, shared symbols, and catastrophic flood stories that resonate from Mesopotamia to Egypt and even Peru.

‘This could explain why so many civilizations tell similar flood stories, the memory of a real, devastating event that reshaped the human world,’ said LaCroix.