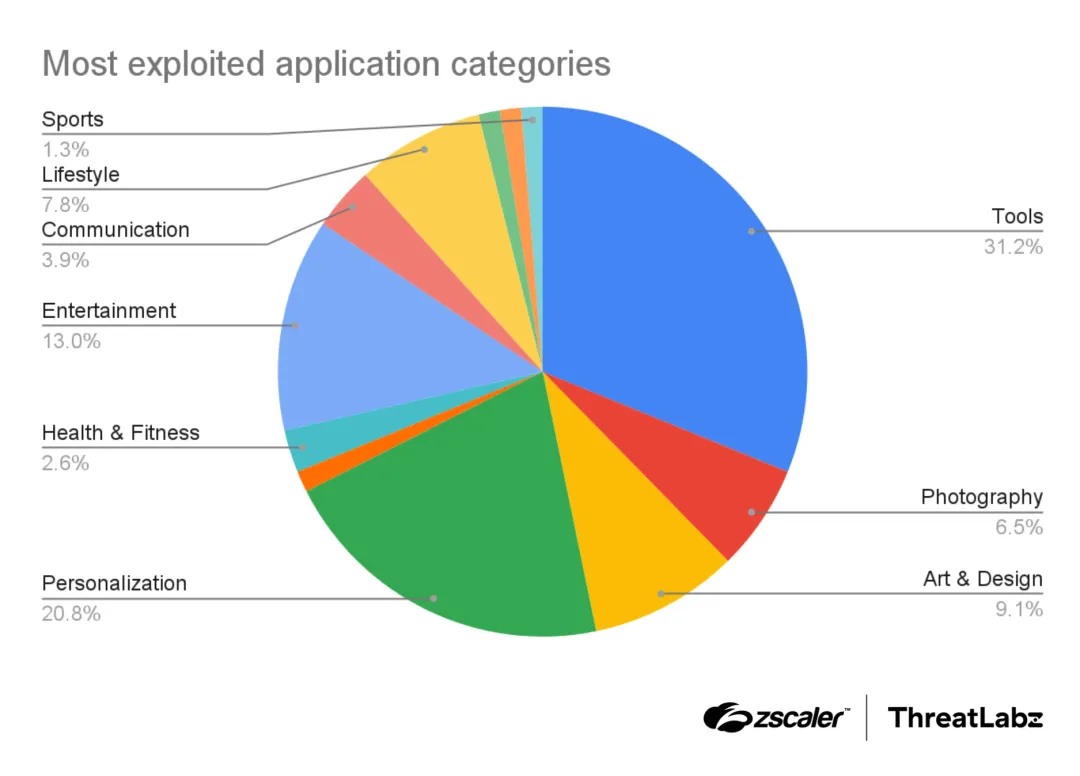

The discovery was made by Zscaler’s ThreatLabz researchers. They counted seventy-seven apps in all. At first glance, most of them looked like utilities, file readers, or personalization tools. That surface layer worked fine, which is partly why people installed them. Behind that, though, there were several different strains of malware.

The bulk were adware, the sort that clogs a phone with intrusive pop-ups. Annoying, yes, but not devastating. A quarter of the apps, however, carried Joker, a long-running threat that can slip into text messages, place calls, or quietly sign up users to premium services. A related family called Harly hid its malicious code deeper inside seemingly harmless apps. Then there was maskware, software that disguises itself well enough to avoid suspicion, but steals credentials or banking details in the background.

And hanging over all of this was Anatsa, also known as TeaBot, the banking trojan that’s been steadily mutating for years. In earlier outbreaks it relied on remote code loading; the new campaign has shifted to unpacking payloads directly from JSON files, erasing traces once the job is done. It isn’t just the method, it’s the reach: from six hundred and fifty financial and crypto apps previously, the target list has now stretched to more than eight hundred. Germany and South Korea have been added to the countries in its sights.

Anatsa’s tactics read like a checklist of modern evasion. Malformed APK archives that break static analysis. Runtime string decryption to keep code hidden until the last moment. Checks to make sure it isn’t being run in a testing environment. Once in place, the malware abuses Android’s accessibility permissions to take control, logging keystrokes and laying fake login pages over banking apps. The result is stolen credentials, and from there, fraudulent transactions.

Google says all the apps flagged by Zscaler have been deleted. Play Protect, the security feature built into Android, should already block the known versions. But removal from the store is only part of the fix. If one of these apps is still sitting on a phone, it stays active until the user deletes it. That means checking through recent installs, paying special attention to document readers or file managers, and reviewing any unusual permissions. Accessibility access, in particular, should raise questions if an app doesn’t clearly need it.

There’s a bigger change coming too. Starting in September 2026, Google will require all Android apps, not only those on Play Store but any installed on certified devices, to be linked to a verified developer account. It’s a step meant to make it harder for throwaway identities to push out malware or low-value apps. Whether that stops every threat is another matter, but it shifts the barrier a little higher.

Anatsa is hardly new, and this isn’t its first appearance on Play Store. In 2023 and 2024, it showed up disguised as PDF readers, QR code tools, even phone cleaners. Each time, thousands of devices were compromised before the apps were pulled. Joker and Harly have their own long histories of slipping through. And security firms are already pointing to Hook, another banking trojan with even broader remote-control tricks.

The pattern is familiar: Google catches up, malware is removed, new apps appear under different names. The cycle repeats. For users, the advice hasn’t really changed. Stick to developers you recognize. Check the reviews, more than one or two. Keep Play Protect running. And above all, watch the permissions. Because while the rules may be tightening and the store getting cleaned, malware on Android isn’t going away. It just keeps finding new disguises.

Notes: This post was edited/created using GenAI tools.

Read next: Imgur Users Rebel Against MediaLab Over Moderation, Glitches, and Lost Community Spirit