Design by: Ibrahum Yahya

PUBLISHED August 24, 2025

KARACHI:

Like every other morning in Pakistan’s largest city, Karachi’s residents set out for work on August 19 with the usual routine in mind. The drive back home, often slowed down by traffic, was a familiar nuisance for those used to the metropolis. Karachi is not a city of frequent rains—showers are mostly limited to the monsoon season—and this year, citizens had been enjoying overcast skies for weeks. But that evening, as thunderclouds gathered, few imagined how dramatically the day would end.

The forecast had warned of rain, yet most people did not take it too seriously. The Met department’s predictions often miss the mark, and so many chose to step out for work anyway—some by preference, others compelled by employers who expect presence at all costs. After all, working from home is not always reliable in Karachi, where internet services are patchy even on clear days. Pakistan lags far behind other nations in internet penetration and speed, and when seasonal rains combine with routine power outages, connectivity becomes even more fragile.

What no one foresaw, however, was that the downpour in Karachi would trigger not just flooded streets and power breakdowns, but people suddenly found themselves struggling to stay online. In some regions, connections slowed to a crawl, in others, services went dark altogether. Businesses, students, and households were left cut off, asking a question few had considered before: how could a weather event in Karachi bring Pakistan’s internet to its knees? That is the question this story seeks to answer.

The scale of the outage

By the evening of August 19, reports of sluggish or failed connections had spiraled into a nationwide crisis. Connectivity levels crashed to just one fifth of normal, a digital paralysis felt from Karachi to Peshawar, Lahore to Quetta. Users found themselves unable to video conference, submit online tasks, or complete everyday banking and e commerce transactions.

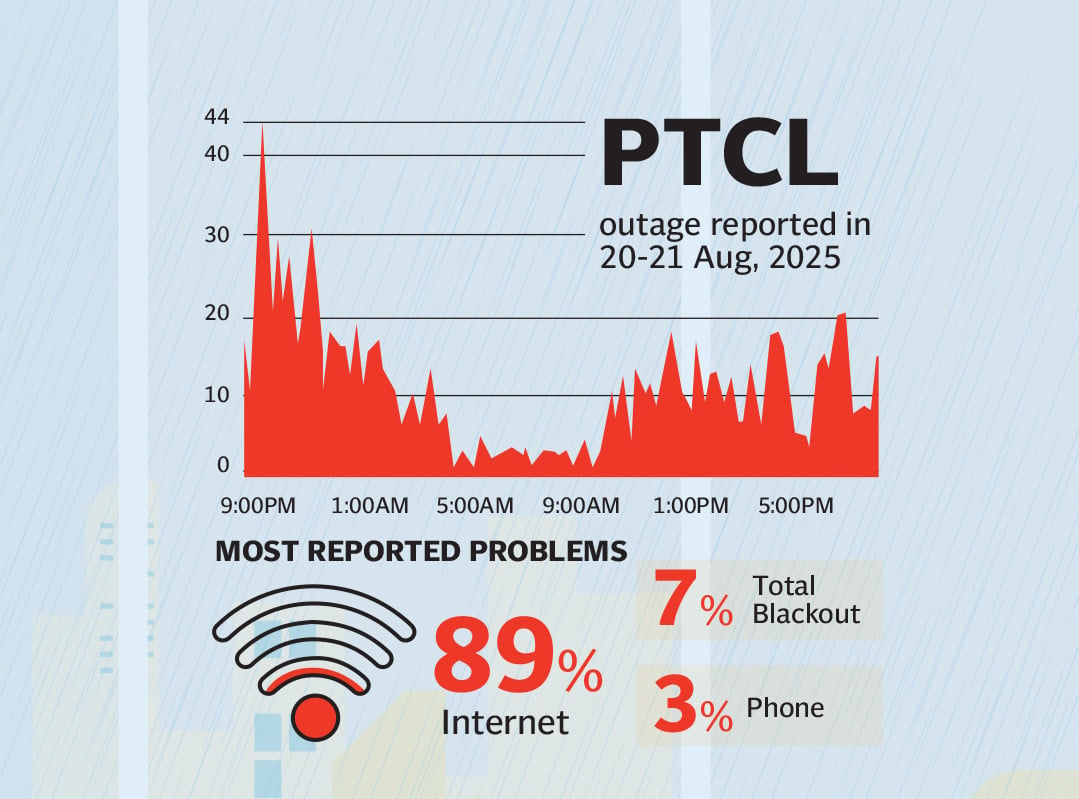

The fallout was uneven. In many regions, the internet slowed to a near standstill. In others, it simply disappeared. Operators such as PTCL and Ufone were hit the hardest, but even Jazz, Zong, and Telenor struggled since their dependence on PTCL’s backbone meant the failure cascaded across the country.

The chairman of the Wireless and Internet Service Providers Association of Pakistan, Shahzad Arshad, called the disruption “a national failure.” He further warned, “Internet outages are no longer rare accidents in Pakistan. They have become a recurring reality. For two thirds of the country to go dark in 2025, on the very date we saw the same collapse in 2022, should ring alarm bells at every level of government.”

With more than 116 million internet users in Pakistan, the consequences were not just technical but deeply economic. Freelancers missed international deadlines, hospitals lost access to digital records, banks struggled with transactions, and e commerce platforms froze mid order. Previous assessments had already placed the annual economic cost of internet disruptions at 1.62 billion dollars. The August 19 outage reinforced how fragile Pakistan’s digital backbone remains in the face of environmental shocks.

There was also sharp disagreement over how widespread the damage in Karachi truly was. Some telecommunications experts insisted that only 22 percent of towers in Karachi were affected by flooding and power outages, claiming that the majority continued to function. Yet inquiries across Gulshan, Clifton, Korangi, North Karachi and other neighborhoods told a different story. Nearly three fourths of residents reported either total loss of internet or speeds too slow to use.

This gap between the official assessment and the lived experience highlights deeper issues of both infrastructure resilience and transparency during emergencies. As Arshad cautioned, “Every hour offline costs Pakistan millions and damages our reputation internationally.” For a nation that increasingly relies on digital connectivity for its economy, education and communication, such fragility is not sustainable.

What went wrong?

The internet disruption that spread across Pakistan on August 19 was not caused by a single point of failure, but by the combination of fragile systems that collapsed one after another once the rain began in Karachi.

The first cracks appeared when power outages swept across the city. Telecom towers are designed to switch automatically to backup generators when electricity fails, but those generators only work as long as they are supplied with fuel. Once the roads flooded and fuel tankers could no longer reach the towers, the generators sputtered out. Towers that might otherwise have stayed functional for hours or even days simply shut down, leaving entire neighborhoods offline. A resident from Gulshan recalled, “I had full bars on my phone but could not load a single web page after the rain. Later I found out the tower near me had run out of fuel.” In Korangi, another user said, “My internet did not come back for two days because the fuel truck was stuck in the water. It felt like we were cut off from the rest of the city.”

There are towers in Karachi that run on solar, and they proved more resilient than the rest. Even when the grid went down and fuel deliveries were impossible, those solar towers kept running. But their number is very small, barely enough to make any difference to the wider population. “We have only a handful of solar towers in Karachi. When everything else fails, they survive, but they are too few to matter,” a technician explained.

The problem was made worse by the fact that too many people tried to stay online at the same time. As services in some areas flickered on and off, users rushed to reload pages, rejoin meetings, or shift to mobile networks. This sudden surge in demand created bottlenecks on the already weakened backbone. IT Minister Shaza Fatima acknowledged this, saying there were “too many users” pulling on a system that simply did not have the capacity to bear the load.

“The other localised issue is temporary choking of the network as too many people were stranded at the same spot and almost everyone was either making calls or receiving them. And now with PTCL going dead, all connectivity has shifted at telephony creating more choking,” the Minister added.

What ties these failures together is the centralized nature of Pakistan’s digital infrastructure. The country has tens of thousands of telecom towers, but traffic is funneled through a limited number of core hubs. When one of those hubs falters, as it did in Karachi during the rain, the impact ripples far beyond the city. The flood not only drowned streets but also stranded engineers and technicians who could not physically reach the sites that needed repair. Even in places where towers were still standing, access roads were under water, and crews could not get close enough to restore services.

As one freelancer from Lyari put it, “They said service was restored, but my files would not upload and my clients thought I had disappeared.”

The collapse of Karachi’s towers and the fragility of the backbone network did not remain a local issue. As generators failed, signals dropped, and users overloaded surviving systems, the consequences began spilling far beyond the city. What started as a rain-soaked disruption in one metropolis soon grew into a chain reaction that slowed down or silenced the internet across Pakistan, setting the stage for a nationwide fallout that affected businesses, households, and daily life on an unprecedented scale.

Nationwide fallout

What began as a weather shock in Karachi quickly turned into a national crisis. As connectivity collapsed in the south, signals across Lahore, Islamabad, Quetta, and Peshawar slowed to a crawl or dropped altogether. Users who thought the rain was only Karachi’s problem suddenly found themselves disconnected hundreds of miles away.

The reason lay beneath the sea. Pakistan’s international internet depends on three main submarine cable providers—PTCL, Cybernet, and Transworld Associates. All of them operate their hubs out of Karachi. PTCL carries the largest share of the load, which means when its systems falter, every other operator is pulled down with it. On August 19, the storm that drowned Karachi’s roads also exposed how the country’s dependence on one city for its connectivity made every user, everywhere, vulnerable.

The fallout was immediate. Freelancers in Islamabad and Rawalpindi reported losing hours of work. “I had two live projects running, one with a US client and another with Europe. Both failed because I could not upload files,” said a digital designer Rahima in Islamabad. A Lahore resident Ali shared, “Even though we had electricity, the internet vanished. We kept checking the router and phones, thinking it was our fault, but the problem was everywhere.”

The disruption rippled through businesses too. Banks were unable to process mobile transactions, merchants saw online payments decline, and retailers using e-commerce platforms had orders freeze mid-process. Educational institutions, which had increasingly come to rely on blended learning, canceled or postponed online classes.

Frustration poured out once services partially returned. Social media feeds filled with complaints and disbelief. “We were told Karachi was the only city affected by rain, but why did our internet die in Lahore?” asked one user on X. Another in Islamabad wrote, “We had no rain, no power cut, yet we were offline for hours. This is not weather, this is poor planning.”

Calls grew louder for serious reform, with digital rights groups and telecom associations urging the government to diversify infrastructure, enforce stricter regulations, and ensure redundancy so that a failure in Karachi does not paralyze the rest of the country again.

The nationwide reaction showed that this was not merely a local glitch but a collective breakdown. A rainstorm in one city should never have been able to cut across the entire country, yet that is exactly what unfolded.

The anger and frustration that followed the outage showed that people were no longer willing to accept disruption as routine. From businesses losing clients to students missing classes, the cost of being offline was felt in every corner of the country. What August 19 exposed most clearly was that Pakistan’s internet is built on fragile foundations and that a weather event in one city should not be able to silence an entire nation. The question now is how to make sure it does not happen again, and what steps are needed to prevent the next crisis from bringing the country to a standstill.

Restoration and response

Both PTCL and the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) were quick to acknowledge that something had gone wrong. PTCL issued a statement in the afternoon confirming that users were facing problems, explaining that “due to heavy rains and flooding in Karachi, internet services are impacted.” The company added that its teams were “working to resolve the issue on priority and restore services as quickly as possible.”

The PTA also released a same-day update, saying it was in contact with operators to monitor the situation. It explained that connectivity issues were the result of a “technical fault in the south region” and assured users that efforts were underway to stabilize the system.

By the following morning, PTCL announced that services had been fully restored across Pakistan. “We are pleased to confirm that internet services have been normalized nationwide,” its statement read, stressing that engineers had worked continuously through the night. The PTA echoed this optimism, reporting that 80 percent of telecom services in Karachi had been restored within hours of the initial disruption.

Yet, despite these assurances, many users across Karachi and other cities continued to struggle well after officials declared victory. Even on August 23, complaints of slow connections and prolonged outages were still being reported. A user from Karachi’s Gulistan-e-Johar neighborhood voiced the frustration bluntly, “They said everything was back, but my connection has been crawling for days. For me, the outage never really ended.” Similar accounts surfaced from Malir, DHA, North Karachi, Nazimabad and Gulshan-e-Iqbal as well, where residents described services that were technically restored but practically unusable.

The official claims may have closed the immediate crisis on paper, but for ordinary Pakistanis the experience exposed a deeper fragility. The gap between official statements and the lived reality of users underscored a hard truth: Pakistan’s digital infrastructure is not only fragile but also lacks the safeguards needed to withstand shocks. Each outage chips away at public trust and weakens confidence in the country’s ability to operate in an increasingly digital world.

The experience of August 19 showed that quick fixes and temporary restorations are not enough. What is needed now is a serious conversation about how to strengthen the system, diversify its foundations, and ensure that a single event in one city cannot hold the entire country hostage again.

Solutions & future-proofing

If Pakistan is to avoid repeating this cycle, the system must be rebuilt on the principles of redundancy, diversification, and resilience.

Other countries have already faced similar challenges and invested heavily in solutions. In the United States and Europe, for example, internet backbones are deliberately spread across multiple cities and regions. This means that even if one hub is damaged by flooding or storms, traffic can be automatically rerouted through alternate routes without the user noticing.

Singapore, which faces regular tropical rains, has built disaster-resilient data centers elevated above flood levels and backed by multiple power sources to prevent shutdowns. Japan, prone to earthquakes and tsunamis, has invested in underground cable protection and decentralized landing stations that allow networks to stay live even if a single site fails.

Pakistan, by contrast, has concentrated most of its submarine cable landing stations and backbone hubs in Karachi. This centralization, coupled with dependence on a single dominant provider, leaves the entire country exposed. The reliance on diesel generators for telecom towers is another weak point. In countries like Germany or South Korea, many towers are backed by hybrid systems that combine grid power, solar, and long-duration batteries, which drastically reduce the risk of downtime. Pakistan has only a handful of solar-powered sites, and those too are scattered, not scaled.

What Pakistan needs is a multi-layered upgrade. Submarine landing stations must be diversified beyond Karachi so that a weather event in one city does not cripple the nation. Towers must be equipped with renewable backups such as solar and battery systems, reducing reliance on vulnerable fuel supply chains. Data centers need to be built with flood resilience in mind, using global models that elevate equipment above risk zones and guarantee uninterrupted cooling and power. Perhaps most importantly, the government and regulators must mandate redundancy across all major operators, ensuring that no single failure cascades through every network at once.

Call to action

The events revealed a reality that Pakistan can no longer afford to ignore. What began as a rainstorm in Karachi cascaded into a nationwide disruption, silencing offices, schools, and households across the country. For a few days, millions were reminded that their digital lives hang by a thread, stretched across fragile systems that collapse with the first sign of stress.

This was not just an accident of nature but a failure of planning. The concentration of submarine cables in a single city, the dependence on diesel generators that falter in floods, and the absence of meaningful redundancy meant that the country had no safety net when Karachi went under water. Official statements of swift restoration could not erase the frustration of users who remained offline for days. The gap between what was promised and what was experienced cut deeper than the outage itself.

International comparisons show that solutions are neither mysterious nor out of reach. The same principles that keep Tokyo online during typhoons or New York stable during winter storms can be adapted to Pakistan’s context. Countries facing harsher climates and larger populations have already proven that with investment, planning, and accountability, networks can remain stable even in disaster.

What Pakistan requires now is political will, industry commitment, and a recognition that internet access is no longer optional – it is the backbone of the economy. Without decisive action, every monsoon will carry not just the threat of flooding streets but of shutting down the country’s digital lifeline once again. The question is no longer what went wrong, but whether there is enough resolve to act before the next storm arrives. That is where the story now turns, from diagnosis to responsibility, and from fragile systems to the urgent call for resilience.

To diversify landing stations, to equip towers with renewable backups, to build flood-resistant data centers, and to enforce accountability across providers are not suggestions but necessities. Without these measures, every monsoon will threaten not only to flood the streets but to drown the nation’s digital backbone.

The question that remains is whether Pakistan is prepared to act. The answers are known, the solutions are available, and the urgency has been demonstrated once again. What is at stake now is not just faster internet but the credibility of a country striving to stand on digital foundations. The choice is between accepting fragility as routine or building resilience as a national priority. The storm of August 19 will pass into memory, but the lessons it carries must not.