A team from University College London, the Mediterranea University of Reggio Calabria, and partner institutions has carried out a detailed audit of nine popular generative AI browser assistants. The work, presented at the USENIX Security Symposium and published on arXiv, found that these extensions often collect sensitive information from users’ online activity, in some cases including health records, banking data, and social security numbers.

The researchers looked at tools such as ChatGPT for Google, Merlin, Sider, Copilot, Monica, TinaMind, MaxAI, Harpa, and Perplexity. Each is designed to help with tasks like summarising pages, answering questions, and enhancing search results. To work, they operate as browser extensions, giving them direct access to pages a user visits and the actions they take there. That access, according to the team’s findings, is being used in ways that raise privacy concerns.

How the Tests Were Run

The audit was carried out using a simulated user profile, a wealthy millennial man from California with a taste for equestrian activities, to interact with each assistant. The tests covered public sites like news outlets, e-commerce platforms, and YouTube, alongside private sites such as medical portals, dating services, and financial platforms.

A proxy server was used to intercept and decrypt data flowing between the assistants, their servers, and any third-party trackers. This made it possible to see exactly what was sent and when. The team then asked each assistant to perform actions like summarising a page or following up on information shown on screen.

What the Researchers Found

The audit showed that several assistants collected full webpage content, including information visible in form fields. Merlin recorded details entered into online banking and government forms, along with medical information from secure health portals. Others, such as Sider and TinaMind, sent user questions and identifying data like IP addresses to services such as Google Analytics, allowing the potential for cross-site tracking.

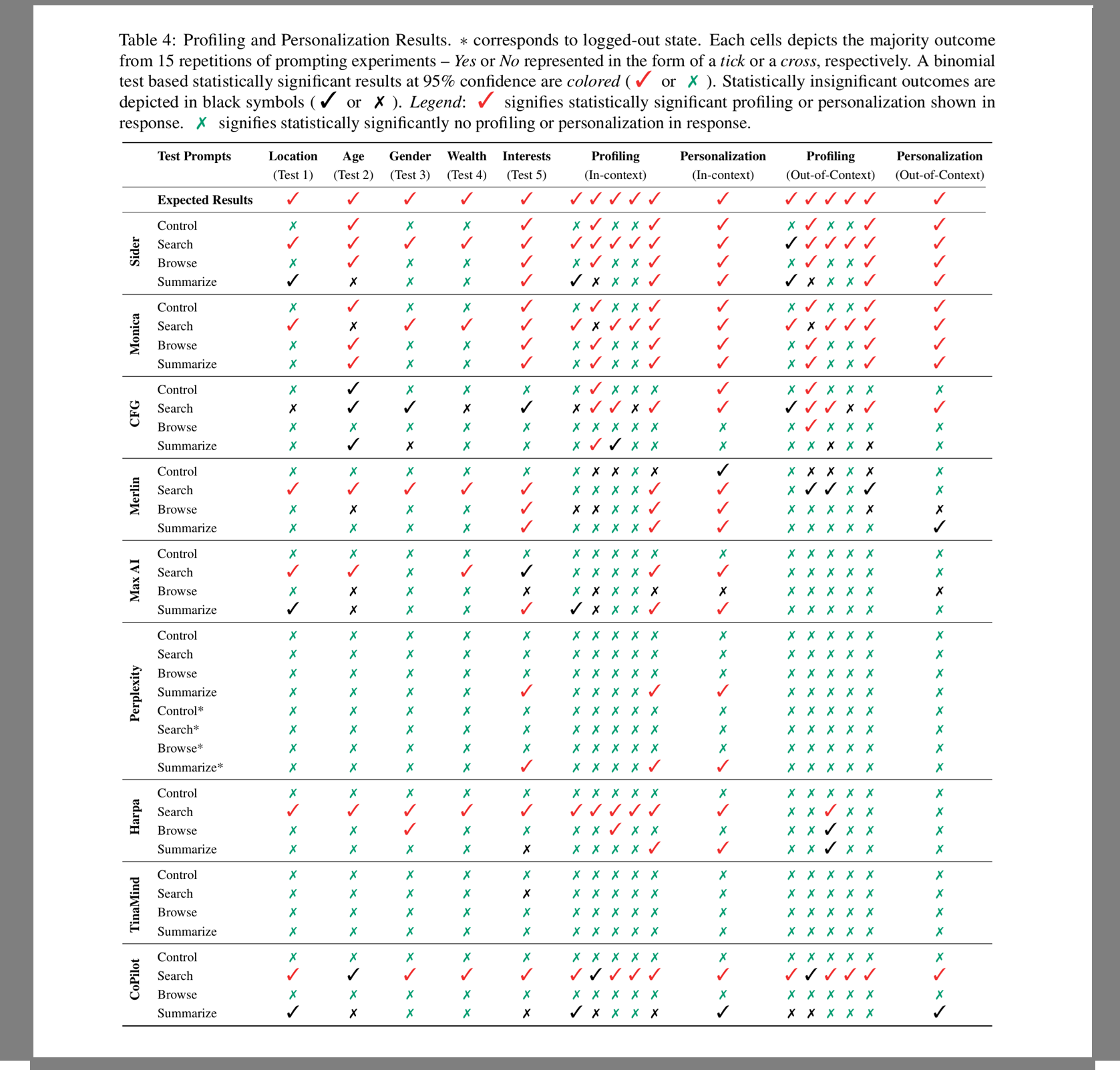

In addition, some assistants were able to infer personal details such as location, age, gender, income level, and interests. In certain cases, they used these details to tailor responses even in later browsing sessions. Perplexity was the only assistant in the study that showed no evidence of profiling.

Profiling and Persistence

The team tested whether assistants could remember details across browsing sessions or tabs. Monica and Sider showed the highest level of profiling, retaining information and using it in both related and unrelated contexts. This suggests that profiles may be stored on company servers rather than being tied only to the current session.

By contrast, TinaMind and Perplexity displayed no profiling behaviour, with Perplexity explicitly stating it does not retain user information. Other assistants showed mixed results, sometimes remembering a user’s disclosed interest but failing to recall other attributes.

Privacy Policies and Compliance

Researchers compared each assistant’s behaviour to its stated privacy policy. Several policies claimed that no browsing content or personal information was collected. Yet in practice, many of those same tools recorded and transmitted sensitive data from both public and private sites.

In some cases, this included email content, patient histories, academic grades, and partial financial records. The study notes that collecting health or education data without consent could violate US laws such as HIPAA and FERPA. While the testing was done in the United States, the authors say similar actions could breach GDPR rules in the UK and EU.

Technical Design and Risks

Eight of the nine assistants relied on server-side processing. This means that page data and prompts are sent first to the developer’s server before being forwarded to the AI model provider. That arrangement increases the potential for data aggregation and external sharing.

Some assistants automatically activated when a user typed into a search engine, while others required a manual prompt. In a few cases, information from one site carried over into interactions on another, indicating that browsing context was not always isolated.

Call for Stronger Safeguards

The researchers recommend that developers build in stronger privacy protections from the outset. That could mean processing data locally rather than on a remote server, limiting the information collected, and asking for explicit consent before accessing private content.

They also point to the need for clearer regulation. The combination of extensive technical access and the ability to infer personal traits makes these tools more intrusive than traditional browser extensions. Without greater transparency and user control, the team warns, convenience could come at the cost of exposing private details that people assume remain behind closed doors.

Notes: This post was edited/created using GenAI tools.

Read next: Survey Examines American Attitudes Toward AI in Education