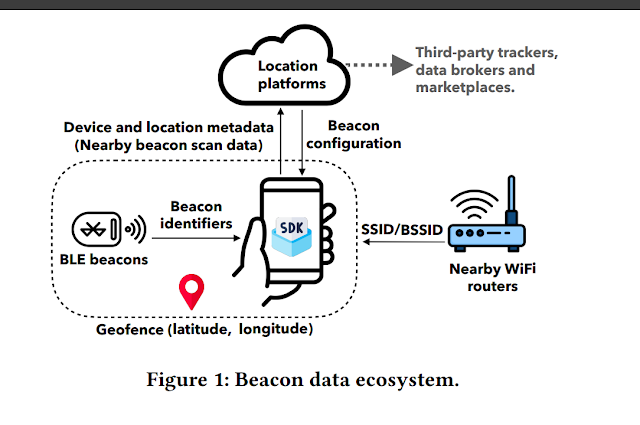

Mobile apps running on Android devices can use Bluetooth and WiFi signals to figure out where someone is, even inside buildings. This works without GPS. A recent study examined nearly ten thousand apps and found that most of them used these signals to collect location data and device identifiers.

Phones often scan for local WiFi networks and Bluetooth beacons. These beacons are small hardware devices installed in public places. Many are fixed in stores, airports, or event venues. When phones detect their signal, apps can estimate a person’s location. Some beacons are accurate enough to locate people inside a specific part of a building.

This tracking happens even when GPS is turned off. The phone does the scanning in the background. Once an app has access to these signals, it can use them as location data. This information gets stored, shared, or sometimes sold.

Tracking linked to advertising software

The research team focused on software development kits. These are the third-party tools that developers use to add features to their apps. The study identified 52 SDKs with wireless scanning capabilities. These were embedded in over 9,900 apps that had been installed billions of times.

In many cases, the SDKs were connected to advertising or analytics services. They collected data that was not essential to the app’s primary function. Researchers found that 86 percent of apps with these SDKs gathered at least one type of personal information. This included GPS location, Bluetooth scan results, WiFi details, and device IDs.

Some SDKs gathered information in ways that Android didn’t fully restrict. They bypassed newer privacy protections by using outdated methods or taking advantage of permissions granted to the app as a whole. Many did not give users a clear reason for needing location access.

Beacon signals used as a location proxy

Bluetooth beacons can broadcast unique identifiers. These identifiers are tied to specific spots, like a checkout area or a departure gate. Apps that detect these signals don’t need to ask for GPS. They can match the beacon ID with a known location in a database.

Beacons are used by retailers, stadiums, and other businesses. They help apps identify whether a person is nearby. That data may then be used to deliver targeted content, track foot traffic, or build profiles. In this study, researchers found that beacon SDKs were most common in shopping, lifestyle, and sports apps.

The SDKs often combined beacon signals with other data points. In some cases, they linked temporary device IDs with permanent ones. This made it possible to track someone over time, even if they tried to reset their advertising ID or reinstall the app.

Gaps in Android’s privacy rules

Android does require apps to ask for permission before using location services. But Bluetooth and WiFi scans fall under different categories. In older versions of Android, some permissions were easier to obtain or had fewer restrictions.

The study showed that many apps asked for more access than they used. Some included location permissions in the app’s code but never triggered the functions that required them. Others didn’t explain why access was needed. Few apps made use of a newer Android feature meant to tell users when Bluetooth or WiFi data is being used for location purposes.

Researchers also found evidence that some SDKs collected nearby WiFi network names and router MAC addresses. This information can be matched with public or commercial databases to determine where a person is. That process doesn’t require GPS and can still reveal location patterns.

Device identifiers used to link data

One of the study’s key findings involved a practice called ID bridging. This happens when a tracking system connects resettable IDs, like the advertising ID, with permanent ones, such as device MAC addresses or boot-time identifiers. The result is a more persistent tracking profile.

Some SDKs shared this information across multiple apps. Others appeared to use their own identifiers, separate from Android’s official system. That allowed them to maintain profiles even when a user tried to limit tracking.

In certain apps, the SDKs collected GPS location, email addresses, and router data all at once. This combination gave them a detailed view of user behavior. Even when users declined access to location, some SDKs still gathered enough data from wireless scans to infer location indirectly.

Researchers call for tighter rules

The team recommended new measures to improve transparency and reduce data misuse. These included isolating SDKs from the main app logic, restricting cross-library data sharing, and requiring more detailed permission requests.

They also suggested more thorough audits of apps that use wireless scanning tools. Clearer user-facing explanations about how and why data is collected could help people make informed decisions. Right now, most users aren’t aware that Bluetooth and WiFi signals can expose their movements inside buildings.

Even with newer privacy policies in place, the findings show that many apps are still collecting more data than they need. In most cases, the data flows happen behind the scenes and without direct user interaction.

Notes: This post was edited/created using GenAI tools.

Read next: Single Wireless Packet Can Shut Down Smartphone Modems, Researchers Say