On July 31, one day before the Aug. 1 deadline for a batch of new tariffs to take effect, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit will hear oral arguments in the case. The Trump administration lost the first round in May at the Court of International Trade. (That decision did not affect other Trump tariffs, such as those on steel, aluminum and cars, and proposed tariffs on pharmaceuticals and semiconductors; Trump imposed these using other legal authorities.)

The appeals court will be the last stop before expected consideration by the Supreme Court.

Here’s a primer on how this case could affect Trump’s tariff policies.

Does the International Emergency Economic Powers Act allow tariffs?

Whether the law permits the imposition of tariffs may be hard for the administration to prove.

The law “authorizes the president to take various actions, but with no mention of ‘tariffs,’ ‘duties,’ ‘levies,’ ‘taxes,’ ‘imposts’ or any similar wording,” University at Buffalo law professor Meredith Kolsky Lewis said. “No president has sought to impose tariffs pursuant to the law” before Trump, she said.

The administration’s strongest argument may be that although the law “doesn’t specifically authorize tariff measures, it doesn’t bar them either,” said David A. Gantz, a Rice University fellow in trade and international economics. “Some have questioned whether Congress intended to cede basic Commerce Clause powers so completely to the president, but the statute does not appear to ever have been seriously challenged in Congress with repeal.”

Does the present situation constitute an emergency?

The second issue might be more challenging for Trump: Are trade deficits a security threat?

In asserting the authority to impose tariffs, Trump said “large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficits constitute an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and economy of the United States.”

Babson College economist Kent Jones was skeptical. “Those with knowledge of trade economics scoff at the notion that a trade deficit is a national emergency,” he said. “The U.S. has run trade deficits consistently for the last four decades, without signs of an economic emergency that can be systematically linked to the deficits.”

The tariffs applied to dozens of countries that ship more goods to the U.S. than they import, which “suggests a lack of an ‘unusual’ threat,” Lewis said. “In other words, this is commonplace.”

Using fentanyl trafficking and trade deficits as examples of emergencies breaks new ground, said Ross Burkhart, a Boise State University political scientist who specializes in trade.

Although the law “does not delineate what a national emergency is, the precedent from previous administrations is not to invoke a national emergency based on day-to-day trade flows,” Burkhart said.

An even more aggressive argument in the case of Brazil

Trump’s threat of a 50% levy on Brazil may be on thinner legal ground, legal experts said.

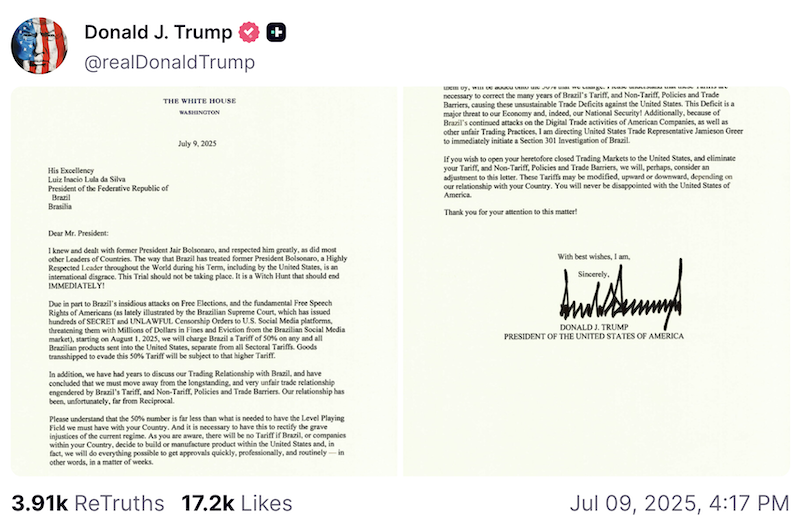

On July 9, Trump wrote a letter to Brazil’s president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, explaining that the new tariff would be “due in part” to Brazil’s prosecution of former President Jair Bolsonaro, a Trump ally, as well as its treatment of U.S. social media companies. The letter also cites a “very unfair trade relationship” with Brazil.

(Screengrab from Truth Social)

Experts said that all of these justifications ring hollow legally under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act. The Brazil policy isn’t at issue in the current case, but it has already attracted at least one lawsuit.

“It does not appear that President Trump has even declared a national emergency — a requirement of the law — tied to any of the issues raised in his letter,” Lewis said.

And experts doubted that citing the Bolsonaro case as an emergency would survive judicial scrutiny. Bolsonaro sought unsuccessfully to hang on to power after Lula defeated him in 2022, which prompted years of investigations and charges that could land him in prison.

“I and many others would agree that the Bolsonaro trial — even if (it were) questionable, and it isn’t — would not come close to meeting” the standard under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, Gantz said. So Gantz said he expects that if the administration follows through on the tariff threat, it will remove the Bolsonaro prosecution as a justification in the legally binding order.

Trump’s letter undercuts another key fact in the U.S.-Brazil trade relationship: The U.S. had a $6.8 billion trade surplus with Brazil in 2024, and surpluses in earlier years as well.

Certain U.S. sectors, such as social media and electronic payment networks, may have plausible gripes with Brazil over trade policy. Even so, Gantz said, “all of these grievances together seem to me insufficient for action under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act.”

What happens next?

Most legal experts we talked to said the appeals court would have ample reason to follow the Court of International Trade’s lead in striking down Trump’s authority. “I am quite confident that the law doesn’t give a limitless grant of authority to the president simply by saying some magic words,” said Julian Arato, a University of Michigan law professor.

But that result is no certainty — and ultimately, the U.S. Supreme Court will have the final say. The conservative-majority court should be a friendlier venue for the administration.

If the appeals court doesn’t reverse the Court of International Trade’s ruling, “the Supreme Court will, in my opinion, likely do so,” Gantz said.

And even if the Supreme Court were to rule against Trump, he could still impose tariffs under other laws.

He could use Section 301 of the 1974 Trade Act, which allows tariffs when the president determines that a foreign country “is unjustifiable and burdens or restricts United States commerce” through violations of trade agreements. This authority has been invoked dozens of times by various presidents.

Or he could use Section 232 of the 1962 Trade Expansion Act, which lets the president impose tariffs if national security is threatened; Trump and President Joe Biden used this as the basis for steel and aluminum tariffs imposed since 2018.

These more traditional mechanisms have been more battle-tested in court than the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, Gantz said, providing “a more persuasive legal basis for the tariffs.”