Artificial intelligence can write, translate, and reason at astonishing speed, yet when it comes to simple conversation, it still misses the mark. A new study[1] from researchers in Norway, Switzerland, and Switzerland’s University of Basel reveals that even advanced language models such as ChatGPT-4 and Claude Sonnet 3.5 fail to mimic how people naturally talk on the phone.

The research, published in Cognitive Science, compared transcripts of real human phone calls from the Switchboard corpus with over a thousand AI-generated dialogues. The models included both proprietary systems like ChatGPT-4 and Claude, and open-source versions such as Vicuna and Wayfarer. Each system was prompted to produce 50-turn conversations between strangers on casual topics such as hobbies or food.

Overly Polite, Poorly Timed

When human participants talk, they subtly mirror each other’s language. They repeat certain words, adjust their tone, and pick up on social cues in a way that feels natural. The study found that AI systems overdo this adaptation. Researchers called it “exaggerated alignment”… a tendency to agree too quickly or to echo phrasing too precisely.

In human speech, alignment gradually builds up as a conversation unfolds. AI models, however, start highly aligned and become even more so. The researchers found that syntactic alignment in GPT-4 and Claude increased sharply from early to later turns, whereas in human dialogue it stayed relatively stable. This mechanical imitation often makes AI dialogue sound rehearsed rather than spontaneous.

Another problem is timing. Human conversations involve rapid exchanges and short turns, averaging around 14 words per sentence. In contrast, AI turns were much longer… GPT-4’s responses averaged more than 50 words per turn, while Claude’s stretched beyond 80. This created an unnatural rhythm closer to written text than spoken dialogue.

Filler Words that Give Us Away

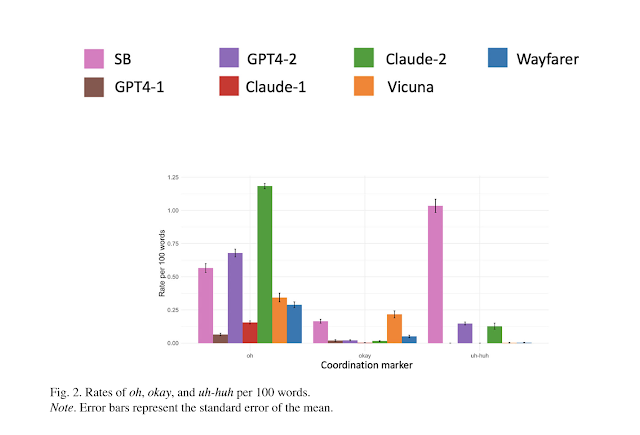

A striking difference came from the use of small social words such as “oh,” “okay,” and “uh-huh.” In real phone calls, these markers occur constantly, about one “uh-huh” per 100 words, according to the data. They signal understanding, emotion, or a change in thought. AI models rarely used them correctly.

For instance, GPT-4 produced “uh-huh” almost never, and when it did, it often followed with a full sentence instead of letting the sound stand alone as a human listener would. One of Claude’s versions began nearly eight in ten turns with “oh,” an awkward overuse that no human speaker would replicate. These small errors make even the most advanced chatbots sound subtly artificial.

Openings and Closings Still Robotic

Another area where the models stumbled was in how they start and end conversations. Humans open calls with greetings, casual checks like “how are you,” or short personal remarks before moving to the main topic. AI systems either skipped this stage or applied it formulaically. They used stock lines such as “nice to meet you” or “where are you from” almost every time, creating an impression of scripted politeness rather than genuine small talk.

Ending a call proved equally tricky. Real conversations often wind down gradually with phrases such as “okay then” or “talk soon.” AI systems tended to cut off abruptly or, at times, extended the conversation with unnecessary pleasantries. The word “okay,” present in 83 percent of human closings, appeared rarely in AI endings.

People Can Still Tell the Difference

To test whether humans could spot the difference, the researchers asked over a thousand English-speaking participants to judge random snippets of both real and AI-made conversations. Most people correctly identified which ones were synthetic. Only about one-third of AI dialogues were mistaken for human speech, while even genuine human calls were sometimes misread as robotic – perhaps because both follow certain conversational templates.

Interestingly, shorter excerpts were harder to judge than long ones. When participants read longer passages of 400 words, accuracy improved. The more context people saw, the easier it was to detect patterns of exaggerated politeness or repetition.

Why the Gap Persists

Part of the problem lies in what current large language models learn from. Their training data mostly consist of written text (articles, websites, and fictional dialogue) rather than live, spoken conversation. As a result, they imitate written structure rather than the spontaneous rhythm of speech. They also lack what psychologists call “the interaction engine,” the social drive that enables humans to interpret intention, emotion, and shared context in real time.

Even with stronger models and more speech data, that missing human layer may remain difficult to simulate. Speech is not just a string of words but a performance that reflects memory, emotion, and body language. Language models have none of these cues.

The Road Ahead

Future improvements could narrow the gap. The researchers suggest that better datasets of real spoken exchanges and more fine-tuned prompting may help AI respond more naturally. Yet the study also points to a deeper limitation: conversation is a social act rooted in shared understanding, not only in language structure.

For now, large language models can hold coherent discussions, but they do not truly converse. Their rhythm is too slow, their politeness too consistent, and their timing slightly off. Until AI can learn not just what to say but when and how to say it, people will keep recognizing the difference.

Notes: This post was edited/created using GenAI tools.

Read next: The Way We Talk to Chatbots Can Shape How Smart They Become[2]

References

- ^ study (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ The Way We Talk to Chatbots Can Shape How Smart They Become (www.digitalinformationworld.com)