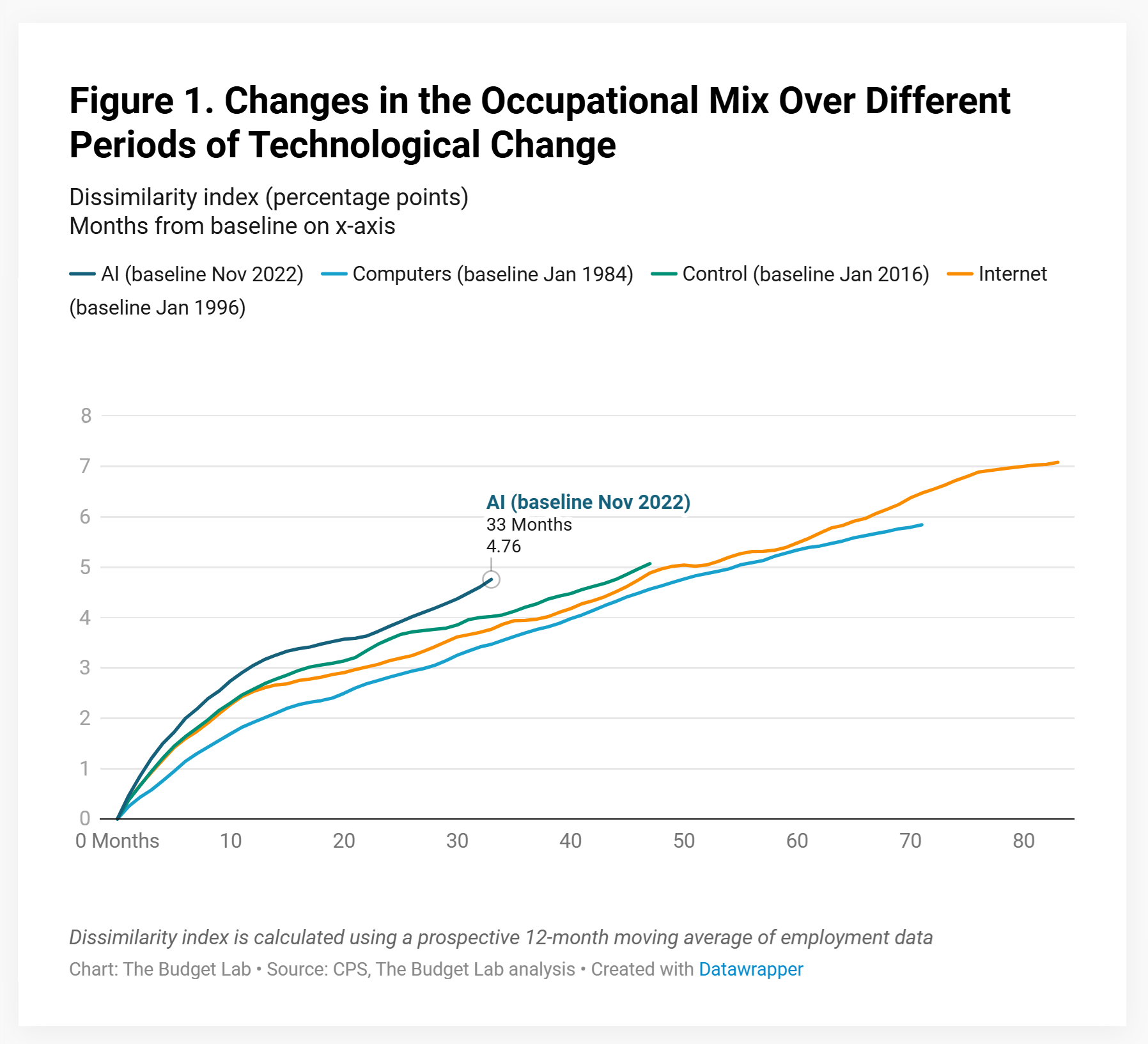

New labor market evidence suggests that AI is transforming the world of work faster than any previous wave of technology. Data from the Yale Budget Lab’s 2025 report[1] and a companion analysis of U.S. labor metrics show a striking shift in the composition of jobs within just three years of widespread AI deployment.

The dissimilarity index, a standard measure of how far job distributions have diverged from a baseline, reached 0.26 by the 33rd month after AI’s breakout moment in late 2022. For comparison, computer adoption during the 1980s reached similar levels only after almost a decade. Internet-related shifts took roughly twice as long. This marks the steepest occupational reshaping since systematic data began in the early 2000s.

The acceleration points to more than simple automation. Jobs are changing from within, forcing skillsets and workflows to reorganize faster than in any earlier technological cycle. The data implies that AI’s reach extends not only into repetitive work but also into professional, analytical, and creative fields that were once insulated from automation trends.

The Information Sector Moves First

Among all industries, the information sector has taken the lead in reshaping its labor structure. Figures extracted from sectoral breakdowns show that its dissimilarity score stands at 0.35, almost three times higher than that of manufacturing and roughly double that of education and health services.

This reflects a rapid internal turnover where editing, software, data analysis, and design roles have rebalanced toward hybrid human–AI tasks. In these roles, algorithms have become extensions of human work rather than replacements for it. Analysts note that this sector’s early transformation mirrors how manufacturing adapted to robotics decades ago… only now, the shift is cognitive rather than mechanical.

The financial activities sector follows closely, with measurable compositional shifts around 0.28 after the same period. Though less visible than in media or tech, finance has quietly integrated AI into trading, fraud detection, and reporting, trimming some back-office tasks while expanding demand for risk engineers and compliance analysts.

Where Jobs Are Moving

Across the full economy, the data highlights a drift from low-exposure occupations toward AI-heavy roles. The share of workers in the highest exposure quintile has climbed from 27 percent to 33 percent since late 2022, while those in the lowest group have declined proportionally. This six-point redistribution represents one of the fastest reallocations of labor since the rise of broadband in the 2000s.

Such shifts do not necessarily equate to job loss. In most sectors, total employment has remained stable, but job mixes within them have changed. Professional and business services, information, and education-related industries have all absorbed workers into analytical, technical, or coordination roles that rely on AI tools. Sectors built on predictable routines (such as manufacturing, transportation, and clerical support) have seen slower but steady erosion of older tasks.

The Hidden Lag in Worker Adjustment

While job displacement rates remain modest, the path back to work is taking slightly longer for those affected. Data on unemployment duration shows that the proportion of displaced workers remaining out of work for more than 27 weeks rose from 30.2 percent to 32.7 percent between 2022 and mid-2025.

This modest rise suggests friction in retraining rather than structural job loss. In practice, it means that workers whose previous tasks have been redefined by AI often take an extra month or two to reconnect with roles requiring similar skills but new tools. Policymakers see this as a signal that transition programs must evolve faster than in previous industrial adjustments.

Forecasts Were Wrong About Who Would Use AI

One of the most surprising findings concerns the difference between expected and actual AI usage across occupations. According to the Budget Lab dataset, computer and mathematical roles now record an observed AI usage rate of 56 percent, compared with an expected 7.8 percent predicted in early exposure models. Similarly, arts, design, and media roles show an observed share of 6.5 percent versus a 1.9 percent forecast.

Meanwhile, business and financial operations, once assumed to be among the most AI-exposed, have underperformed expectations, registering only 3.8 percent observed usage against a 10.6 percent forecast. These reversals indicate that AI diffusion has followed skill networks rather than managerial hierarchies. Technical and creative workers, accustomed to adaptive tools, have become first adopters, while administrative decision-making remains slower to integrate machine learning systems at scale.

Diverging Models and Exposure Gaps

The data also reveals wide disagreement among model-based exposure estimates. OpenAI’s framework classifies roughly half of all occupational tasks as at least partially exposed to AI, while Anthropic’s model identifies closer to 30 percent. The gap is widest in administrative and data entry roles, which OpenAI sees as heavily automatable but Anthropic rates as less exposed due to human oversight requirements.

Both models converge, however, on one point: the pace of exposure has outstripped any comparable technological benchmark. In earlier decades, computerization affected clear physical workflows; AI, by contrast, redefines mental ones, blurring boundaries between replacement and augmentation.

An Uneven but Expanding Adaptation Curve

By late 2025, the top sectors reporting measurable AI-related shifts, professional services, finance, and information, show a consistent pattern: routine functions decline, while demand for analytical, interpretive, and coordination work rises. Workers at mid-skill levels, particularly those comfortable with digital tools, are experiencing the fastest transitions.

Lower-skill segments continue to face the greatest challenge. Their exposure to AI-driven change is often indirect, felt through the reorganization of supply chains or internal processes rather than direct automation. Yet even in these segments, the data shows gradual movement toward blended roles, as tasks become distributed between human decision-making and algorithmic execution.

A Broader Economic Signal

Taken together, the Yale–Budget Lab findings and the extended dataset suggest that the U.S. labor market is not shrinking but rewiring. AI has accelerated a kind of silent restructuring where job definitions evolve faster than formal occupational codes can record. The index data implies that by 2026, the overall pace of change may double that of the post-internet decade, setting a new baseline for how fast economies can adapt to general-purpose technologies.

Economists tracking the trend argue that the coming years will be defined less by job destruction and more by skill realignment. The displacement data points to manageable friction rather than crisis. Training systems, credentialing bodies, and employers are now adjusting to match the velocity of this shift.

The Rewired Workforce

The core insight from this year’s analysis is that human work has not diminished; it has become more modular and reactive. Each wave of automation in the past targeted physical repetition, but AI’s spread now targets mental repetition. In doing so, it is pushing work toward synthesis, judgment, and adaptation — areas where human agency still anchors value.

If the pattern continues, the most durable jobs in the late 2020s may be those that blend algorithmic literacy with distinctly human interpretation. Far from replacing people, the technology appears to be reorganizing them into new patterns that reflect the logic of digital intelligence rather than the decline of labor itself.

Notes: This post was edited/created using GenAI tools

Read next: Oracle’s TikTok Takeover Raises Questions About Corporate Pro-Israel Influence[2]

References

- ^ Yale Budget Lab’s 2025 report (budgetlab.yale.edu)

- ^ Oracle’s TikTok Takeover Raises Questions About Corporate Pro-Israel Influence (www.digitalinformationworld.com)