A key ocean current in the North Atlantic Ocean is weakening to the point of total collapse due to climate change[1], a new study warns.

Scientists say the North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre – a massive system of rotating ocean currents south of Greenland – has been losing stability since the 1950s.

It is now approaching a ‘tipping point’ – a critical threshold in the system which, if passed, could cause sudden and dramatic climate changes.

The North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre moves heat from the tropics to the North Atlantic, helping to regulate temperatures in Europe and North America.

But this movement slowing down or ‘weakening’ could plunge Europe into another ‘Little Ice Age’, a dramatic period of regional cooling like the one between around 1300 to 1850.

During the last Little Ice Age, rivers froze over and crops were decimated when average temperatures dropped by about 3.6°F (2°C).

Study author Dr Beatriz Arellano Nava, a lecturer in physical oceanography at the University of Exeter, called the findings ‘highly worrying’.

‘Our results provide independent evidence that the North Atlantic has lost stability, suggesting that a tipping point could be approaching, although it remains uncertain when this threshold might be reached,’ she said.

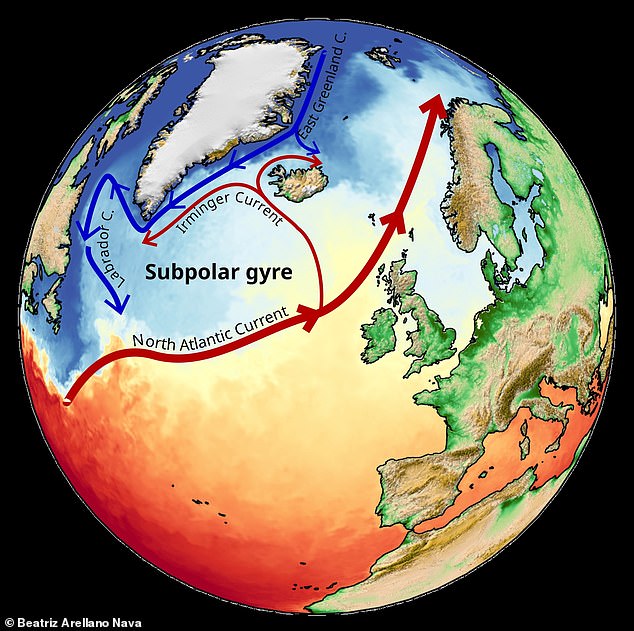

The North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre is a massive system of rotating ocean currents that transports heat from the tropics to the North Atlantic, helping to regulate temperatures in Europe and North America

In oceanography, a gyre is a large system of ocean surface currents moving in a circular fashion driven by wind movements.

The North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre is one of five major subtropical gyres around the world that are part of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) – the vast system of ocean currents that distributes heat around the world, as well as transferring nutrients and carbon dioxide to deeper ocean parts.

Described as ‘the conveyor belt of the ocean’, AMOC delivers warm water near the ocean’s surface northwards from the tropics up to the northern hemisphere, keeping Europe and the US east coast ‘temperate’ – neither very hot nor very cold.

But due to climate change, both systems could pass a tipping point and even collapse[2], which would mean much of the northern hemisphere, including Europe and North America, could experience harsh, freezing cold winters.

For the study, the researchers analysed data from clams found around the North Atlantic region, which have secrets hidden in their shells.

They focused on shells of the ocean quahog and dog cockle, two species of clam that live buried in the North Atlantic seabed.

The clam forms a new shell growth band every year and the width of this band reflects environmental conditions for hundreds of years – much like the concentric rings within a tree trunk[3].

In other words, the chemical composition of the shells encodes information about the state of the seawater in which the clam was growing.

In the Hollywood blockbuster The Day After Tomorrow (pictured), ocean currents around the world stop as a result of global warming, triggering a new ice age on Earth

Researchers based their findings on clam shells recovered from around the North Atlantic region. In this colour map, redness indicates greater loss of current stability preceding rapid circulation changes

Crucially, oxygen and carbon isotopes in the shells provide insights on a range of processes in the marine environment, such as regional changes in circulation.

‘We don’t have ocean observations going back into the distant past, but the bands in clam shells give us an unbroken annual record covering hundreds of years,’ said Dr Nava.

The data revealed that the North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre has had two ‘destabilisation episodes’ over the past 150 years where it has lost stability – suggesting that a tipping point could be approaching.

The first destabilisation episode happened in the early 20th century before the 1920s, while the second stronger episode began around 1950 and continues to the present day.

This suggests that the North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre is moving toward a tipping point that could lead to a cascade of ‘catastrophic, irreversible changes’ to our climate, such as more extreme weather events, particularly in Europe, and changes in global precipitation patterns.

While it would be less catastrophic than the collapse of the AMOC, it would still bring substantial impacts including more frequent extreme weather in the North Atlantic region and deep freezes in Europe.

The UK and northern Europe could experience much harsher winters typical of parts of Canada, while the east coast of the US could see dramatic sea level rises due to changes in ocean circulation.

While the North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre looks likely to ‘weaken abruptly’, it ‘would not completely collapse’ as it is also driven by winds, Dr Nava said.

North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre is part of, and helps power, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation Earth’s vast system of ocean currents that distributes heat and nutrients around the world. The new study finds evidence of ‘stability loss’ that suggests the region is ‘moving towards a tipping point’

The Little Ice Age was a period of major mountain-glacier expansion that spanned from around the early 14th century through to the mid-19th century, when rivers froze over and crops were decimated

Read More

Cost of climate change: Extreme weather cost Europe €43 BILLION this summer, experts warn

‘Such a weakening would reduce the northward flow of heat carried by ocean currents, likely triggering a chain of climate changes including more frequent extreme weather events, stronger seasonal contrasts in Europe, and shifts in global rainfall patterns,’ she told the Daily Mail.

However, a weakening North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre is what occurred during the early years of the Little Ice Age – suggesting similar climate effects could be seen again even if the wider AMOC doesn’t collapse.

The study, published in the journal Science Advances[4], offers independent evidence that the North Atlantic has ‘lost stability over recent decades and is vulnerable to crossing a tipping point’.

‘Melting of polar ice due to climate change is certainly contributing to the weakening of ocean currents and pushing them closer to a tipping point, so rapidly reducing greenhouse gas emissions is the best way to prevent tipping points in the Atlantic Ocean,’ the expert added.

References

- ^ climate change (www.dailymail.co.uk)

- ^ But due to climate change, both systems could pass a tipping point and even collapse (www.dailymail.co.uk)

- ^ the concentric rings within a tree trunk (www.dailymail.co.uk)

- ^ Science Advances (www.science.org)