To say that Justin Portela never imagined himself as a highly paid business consultant at McKinsey & Company would be an understatement. He didn’t have a privileged upbringing, to put it mildly, and in 2018, when he first walked onto the Stanford University campus, Portela, like most incoming freshmen, was unaware such careers even existed. But that would soon change.

His career choice also surprised Eric DiMichele, who’d written Portela a glowing recommendation the previous fall. DiMichele is a revered teacher, debate coach, and director of community engagement at Regis, a prestigious Jesuit high school on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Even among his many successful former pupils—including CNN correspondent Jim Sciutto, former federal prosecutor Patrick J. Fitzgerald, and SNL’s Colin Jost—Portela was exceptional. “With his formidable intellect, breathtaking knowledge, irrepressible passion and bone-deep generosity, Justin receives my highest recommendation in my 36 years at Regis,” DiMichele wrote. Citing his protégé’s tumultuous childhood, he even committed to help pay for his college education, because “I believe so strongly in Justin.”

Hoping to say something in the recommendation about Portela’s commitment to effective altruism—the ethical movement inspired by the work of the utilitarian philosopher Peter Singer—DiMichele messaged Portela for more details. After a couple of hours, Portela sent back a five-page, single-spaced treatise he’d typed on his phone while in transit. The essay was cogently divided into three sections and included a lengthy analysis—based on effective altruism’s principle of applying reason and data to maximize the benefit of charitable actions—of the causes to which he hoped to dedicate his life: world health, sustainable farming, and mitigation of existential risks such as nuclear proliferation, global pandemics, and hostile artificial intelligence.

“With scattershot brilliance,” DiMichele recalled, “he captured the essence of effective altruism.” Stanford accepted Portela three months later.

On paper, Portela seemed destined to become a do-gooder. “Justin could be whatever he wanted,” but he’s “not capable of being selfish,” DiMichele told me. He figured Portela would end up pursuing “purposeful work tied to some social justice issue” and not—as things turned out—a lucrative gig at one of the Big Three management consultancies.

Portela, now 25, offers a simple explanation: “They funneled the shit out of me.”

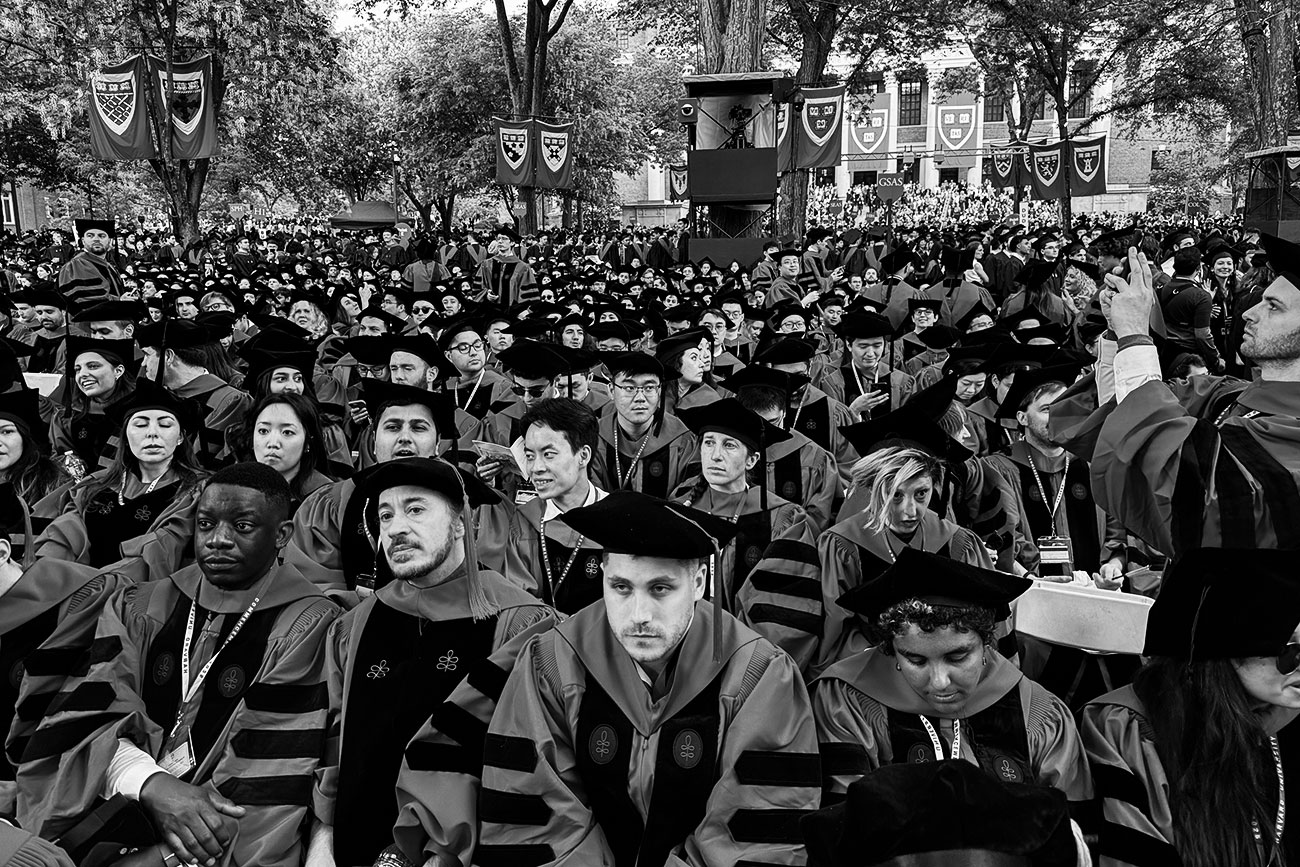

The “career funnel,” a phrase coined by sociologists Amy Binder and Daniel Davis, describes the mechanism behind the crowding of elite college graduates into three high-paying fields. For instance, the Harvard Crimson’s annual survey of graduating seniors revealed that more than half of the class of 2025 had taken jobs in finance (21 percent), tech (18 percent), or management consulting (14 percent).

In the previous year’s survey[2], which yielded similar numbers but included more detailed pay data, more than two-thirds of the graduates entering those three fields had reported starting salaries of at least $110,000 (not including signing and performance bonuses) vs. less than $70,000 for the vast majority of graduates pursuing research or academia (9 percent of the class).

Career funneling by elite colleges is “an important piece of the puzzle in why the public sees higher ed as a bad actor.”

At their core, elite colleges—which sociologist Charlie Eaton has estimated[3] receive a collective $20 billion a year in tax breaks—are machines that perpetuate status and wealth. It’s well known that admissions policies favor the rich, but that’s only part of the story. Elite colleges also steer their students into high-status, high-paying professions that further drive the cycle of inequality. Portela’s story is decidedly atypical in that he grew up socioeconomically disadvantaged and ended up at an elite school and a prestigious firm. During his entire time at McKinsey, he told me, “I have not met a poor person.”

McKinsey did not respond to a request for comment on this story.

Binder, a professor at Johns Hopkins University who has dedicated most of her career to studying college students, argues that the career funnel deeply affects our broader society—and our democracy, now under attack by an administration determined to disparage and defund any institution that refuses to do its bidding. “When elite universities send an inordinate number of their graduates to narrow corporate career tracks, they intensify inequality and divert young people away from serving the common good,” she told me. “It’s an important piece of the puzzle in why the public sees higher ed as a bad actor.”

Today, the public perception of these elite universities is more important than ever. The Trump administration’s attacks on foreign students, scientific research funding, grants and contracts, and university endowments—and its attempts to micromanage campus policy—all have left universities in a state of turmoil. Presuming elite colleges and US higher education survive in something resembling their current form, administrators will have to think broadly about how their educational missions can both serve and be seen to serve the public interest. This will include reconsidering whom they let in and why and what these young people go on to do with their lives.

A common misperception—sometimes emphasized[4] by the colleges themselves—is that the “sellout” culture is student-driven. A widely circulated 2024 New York Times article[5] on what students at elite colleges “really want” captured the prevailing narrative: “Despite the popular image of this generation—that of Greta Thunberg and the Parkland activists—as one driven by idealism, Gen Z students at these schools appear to be strikingly corporate-minded.”

Binder’s and Davis’ work finds such perceptions false in almost every regard. For a seminal 2015 paper[6], they interviewed 56 students and recent graduates of Stanford and Harvard, of which 46 were either working or trying to land jobs in finance, consulting, and tech. Yet none of their subjects had known anything about management consulting before entering college, and only two—whose parents worked on Wall Street—were familiar with the finance world. This was standard among their classmates, they said. In the resulting article[7], published in the journal Sociology of Education, Binder and Davis—a lecturer at San Diego State University who studies college-to-career transitions—concluded that most incoming freshmen have little idea of what they want to do with their lives. Even the wealthiest and highest-achieving ones, they wrote, are “motivated but directionless.”

As a fellow academic striving to make higher education more meritocratic, I found myself taken by their work and even enlisted Binder as an unpaid board member of a nonprofit I co-founded in 2023; Class Action[8] organizes students at elite colleges to urge their administrators away from admissions policies that explicitly favor the wealthy and encourage the colleges to send students into a wide variety of fields, instead of just teeing them up for the Big Three. “I didn’t know there were consulting firms like McKinsey or Bain,” one study participant told Binder and Davis. “I didn’t know that there’s big investment banks like JPMorgan.” Said another young banker: “I didn’t know what consulting even was, or, like, investment banking.”

“These types of jobs are so abstract,” Binder told me. Most people know what professors do, she said: “They teach college students. What the hell does a consultant do?”

Indeed, in the dozens of formal and informal interviews of elite college students I conducted for this article, not one said they’d entered college with the goal of being a consultant or investment banker. The notion that clever and economically motivated Gen Zers are hellbent on corporate careers is simply a fiction that distracts from the real culprit: the colleges themselves.

Portela received an unexpected email about halfway through the second quarter of his freshman year, in February 2019, inviting him to apply for an internship at McKinsey.

He’d been mulling whether to follow his passion and major in English or to instead pursue “symbolic systems[9],” a tech-heavy interdisciplinary program. His application to intern at the US Office of Science and Technology Policy—“my thought was, no one in the Trump administration knew enough about AI to avoid an apocalypse”—had been rejected, so he figured he’d just bum around for the summer. “No venerable institution is going to take a college freshman,” he recalled thinking. But here McKinsey wanted his resumé, transcript, and ACT score (a perfect 36). “If they could ask you for your IQ,” he said, “they would.”

Portela soon found himself at Stanford’s Old Union for the first of three coaching sessions from a Stanford business alum who worked at McKinsey on how to tackle management consulting interview questions.

He explained the rules as we sat in the backyard of my home in Montclair, New Jersey, close to where he grew up. Portela is handsome and dark-skinned—his paternal grandfather is from Puerto Rico and mother is Italian—and sports a mustache that evokes Inigo Montoya from The Princess Bride. He speaks analytically, with a preternatural intelligence—though smarts, as he informed me, have little to do with passing this particular test.

“I knew how to talk like a rich person because I’d spent the last several years talking like a rich person.”

When the interviewer asks, for example, “How many gas stations are there in the United States?” the candidate isn’t evaluated by their answer (roughly 120,000) or even their thought process (say, estimating the number of cars in the US and dividing by how many cars one station might serve), but rather by the performance of certain set pieces. “You have to know your step in the dance,” Portela said.

To illustrate, he posed a condensed version of a question he was given: “Our client is a competitor of SoulCycle. They’re facing competition from a company like Peloton; how would you increase their market share?”

I began musing on how a cycling company might boost its business—uninformed by expertise, though I do own a Peloton. Portela cut me off: “It sounds like you’re supposed to answer immediately.” But he’d learned from his coaching that the first step in the dance is to repeat the hypothetical back to the questioner, demonstrating your grasp of the key components.

You are then expected to ask follow-up questions—say, about how the client’s existing business model differs from that of SoulCycle and Peloton—eliciting material information that was withheld purposefully. Finally, “you’re supposed to say, ‘Can I take a few minutes to organize my thoughts?’” Ditto for the math section: Showing one’s thoughtfulness is as important as the calculation. My quick estimate of the size of the US exercise equipment market would have scored me zero points.

The key to the behavioral portion, which consists of prompts like, “Tell me about a time you overcame a significant challenge,” isn’t to respond in the moment, but, as Portela would learn, to “write the stories beforehand, memorize them, and exaggerate.”

Many wealthier students have a sense of this, he says, from parents or networks, but to low-income students—save the handful who receive coaching—it’s utterly counterintuitive. “This is one of the major ways that consulting firms—and, really, investment banking firms—block low-income students,” Portela said. For all practical purposes, the case study “is in another fucking language.”

His coaching was part of a McKinsey program called the Freshman Diversity Leadership Initiative, which Portela—who describes himself as “half-Latino, kind of”—regards as something of a “scam.”

He was one of 15 Stanford undergrads invited to McKinsey’s San Francisco office for an interview. Only three would succeed. Portela claims he knew in advance whom they would hire: The unsuccessful candidates “didn’t know how to code switch,” he said. Those who were “actually low-income were wearing mismatched suits, unironed shirts, and sneakers. I went to prep school, so I owned a suit.”

This aligns with sociologist Anthony Abraham Jack’s observation that low-income students from elite private high schools—whom Jack calls the “privileged poor”—are better equipped than their less-fortunate peers to succeed at elite colleges. “I knew how to talk like a rich person,” Portela said, “because I’d spent the last several years talking like a rich person.”

Four days after his interview, he received—and accepted—McKinsey’s offer of a 10-week internship that paid $5,750 a month. That summer, he traveled to Los Angeles, where he stayed at swanky hotels and did “almost no work.” He returned to the firm the following summer, this time collecting $17,000 and, at summer’s end, an offer that included a $112,000 salary, a $5,000 “scholarship,” a $5,000 signing bonus, a $10,000 housing stipend, and a potential performance bonus of up to $18,000.

Corporate recruiters tap into a fear of failure hard-wired into students who’ve spent their lives chasing academic success.

The money was transformative. Portela had spent his earliest years in a predominantly white, upper-middle-class suburb. But after his father was convicted of a drug-related offense and served two years in prison, the family became itinerant. They lived in North Carolina for a while, followed by Florida and various parts of New Jersey.

Around his 9th birthday, his parents split up. His mother’s childrearing abilities, Portela told me, were adversely affected by serious mental illness. His sister became a heroin addict—she fatally overdosed in 2023. He eventually moved in with his grandmother in Nutley, New Jersey, affording him some stability.

And now, thanks to McKinsey, he had disposable income for the first time. It was a blessing and a curse. “Almost everyone who starts there has rich parents,” Portela said. For the few low-income recruits, the prospect of repaying the scholarship and housing stipends, which are conditional on staying at the firm a full year—can feel like golden handcuffs. “They get you before you could be exposed to other jobs,” he said, “honestly, before I even knew what I wanted to do.”

That feeling of entrapment isn’t limited to the low-income trainees. A recent “Ivy Plus[10]” alum I’ll call Fred took a job at a proprietary trading firm (one that solely invests its own money) known for its eye-popping pay. During our interview, he expressed ambivalence about his career but said the compensation was difficult to resist. If he stayed five more years, he estimated, he’d take home between $5 million and $20 million. He’d be rich before he turned 30.

The golden handcuffs aren’t just financial. Undergraduate students, Binder and Davis explain, are highly susceptible to social dynamics, including the structured recruitment that begins shortly after they arrive at an elite school. More than half of the 60 colleges Davis surveyed participated in corporate partnerships wherein, for an annual fee, the firms got direct access to student talent.

In exchange for such payments, which Davis and Binder report[11] can add up to millions of dollars, colleges offer a menu of benefits ranging from access to student clubs to displaying corporate logos on campus and preferential placement at recruiting events. “When you go to the career fair,” Portela told me, “companies like Microsoft and Nvidia have prime real estate.”

Corporate recruiters capitalize on students’ insecurities. “When your friend already has a job, you think, ‘Maybe I shouldn’t wait,’” Davis explained. They tap into a fear of failure hard-wired into students who’ve spent their young lives chasing academic success.

“In many respects,” sociologist Lauren Rivera writes, the hiring behavior of top firms resembles how one might choose “friends or romantic partners.”

Davis and Binder’s scholarship draws on the work of the late French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. Because most students at elite universities are raised in privileged environments, they arrive with what Bourdieu calls “habitus,” a well-formed way of understanding and navigating the world. Shockingly, according to a 2017 study by a team of prominent economists, 38 colleges[12] from Barron’s list of “Tier 1” US institutions took more students from families in the top 1 percent of the income distribution than from the entire bottom 60 percent.

Affluent, high-achieving students are conditioned to distinguish themselves via competition—in academics, sports, and extracurriculars—a dynamic replicated in the path to their first job. “Most students haven’t been highly reflective,” Davis said. “They just know [they’re] good at competing.” Indeed, when I asked Fred what had compelled him to work at the trading firm, he replied: “I don’t think I had any real opinions. I’m just going to do what’s the most competitive.” Name brand firms further cultivate the sense of exclusivity by recruiting, as sociologist Lauren Rivera reports[13], only from a handful of top schools.

The effect is to make other jobs seem ordinary. Students at prestigious institutions “don’t want to lose that status,” Davis explained. At least two students told him and Binder they simply couldn’t stomach a job like teaching. “I care deeply about education and education equality,” one interviewee said, but “you can’t just be a teacher after graduating from Stanford.’’

One psychological consequence of the funnel is that many students get wrangled into careers they find deeply unsatisfying. At McKinsey, “the pay is really nice. I’m never bored,” Portela said. “But on net, it makes me unhappy.” He went on: “I feel like an outsider. I’m around these, like, super Machiavellian people that are hyper-ambitious. They have no ethical stake in the ground. The hours are long. I feel inhuman. It skyrockets my anxiety levels.”

His experience is typical of elite young professionals, according to Mustafa Yavaş, a postdoctoral fellow at the Johns Hopkins Center for Economy and Society. “In many developing countries, if you’re good in math and science and if you’re not coming from a wealthy background, you’re either going to become an engineer, a medical doctor, or a lawyer,” Yavaş, who is Turkish, told me. “So, I set sail to become an industrial engineer.” He smiled, adding: “In a parallel universe, I’m one of my subjects.”

After a stint with Procter & Gamble and a brief foray in management consulting, Yavaş switched to sociology and pursued a PhD at Yale University, teaching classes on economic and political sociology. “Over time,” he told me, “I increasingly became aware that these are the good jobs.” But when he met fellow alumni from Boğaziçi University—which Yavaş calls the Yale of Turkey—and interacted with recent graduates of Yale itself, he was struck by the consistency of what he heard. Their jobs were lucrative and prestigious, but “everybody’s complaining,” Yavaş said. The same themes came up repeatedly: “overwork and a much more elusive topic of unfulfillment.”

“Universities want to have representation from Idaho and from West Virginia and so forth. But are they really trying to create thought leaders for those places?”

For his dissertation, Yavaş interviewed more than 100 elite professionals in Istanbul and New York. Although all were Turkish, many attended top US business schools and took jobs at transnational corporations such as Coca-Cola, McKinsey, and Microsoft. The overwhelming theme of Yavaş’s research, published[14] in the American Sociological Review, is what Yavaş calls “occupational regret stories.”

“There were very few people” who were very happy with their situations, he said. The management consultants liked the problem-solving aspects, but “they’re burned out.” One New York corporate lawyer told him she often left work “very late” with “no energy.” During the day, she noted, if “I feel I can’t breathe and I want to take a walk, get some food…I don’t have the chance for this. The only thing I can think of is to finish what I have as soon as possible, go home, and sleep. Because tomorrow is going to be a tough day, too.” A senior sales manager lamented to Yavaş that he hadn’t had a day away from his laptop in five years.

Yale law professor Daniel Markovits reported[15] in his 2019 book, The Meritocracy Trap, that people in “elite” professions now work 12 hours more per week, on average, than middle-class workers do. “Fifty, 60, 70 years ago, you could tell how poor somebody was by how hard they worked,” Markovits said[16] on a 2019 podcast. “Today, that relationship has been completely reversed.”

Portela routinely worked 12-hour days, but it was the intensity that affected him most. “Everything is, like, faster, quicker, sooner,” he said, and “it’s not just about the total time it takes; it’s about the amount of stuff you’re pushing. The exertion is really high.”

Granted, the soundtrack for stories of highly compensated but miserable Ivy Plus alums might be played by the tiniest of sad violins. But the question of who is drawn to these jobs—and who stays—has broader societal implications. In her book Pedigree: How Elite Students Get Elite Jobs[17], sociologist Rivera shows that recruiters from management consultancies, white-shoe law firms, and top-tier investment banks favor candidates with leisure pursuits and presentation styles similar to their own, thereby favoring the already affluent over the high-achieving poor. The interviewers she studied tended to seek “buddies,” “formidable playmates,” and colleagues who “could actually be your friend.”

“In many respects,” Rivera writes, their hiring decisions were akin to the ways one might choose “friends or romantic partners.”

This is yet another reason high-prestige jobs go disproportionately to the privileged. The Harvard Crimson’s surveys[18] show significant disparities in career outcomes by family income. In 2024, 19 percent of graduating seniors from families earning less than $40,000 per year said they would enter academia or research, more than double the share from families earning $500,000 or more. On the flip side, 33 percent of graduates from the wealthiest category planned to go into finance vs. 19 percent from the lowest-income tier and just 8 percent from families making $40,000 to $80,000.

The years just after college have “multiplicative, exponential” effects, says sociologist Amy Binder. They “are really important. You’re thinking about what you want out of your life.”

Obviously, nurturing wealthy alumni is advantageous for top universities and their endowments, but those universities are not exactly struggling. (Harvard’s endowment—$53.2 billion[19] as of September 2024—exceeds[20] the GDP of 122 countries; Princeton’s is worth a staggering $3.8 million per student[21].) It says something about the motivations of top-tier colleges that Binder and Davis’ research has been out almost a decade and cited more than 300 times in subsequent studies, yet schools have done little to nothing in response. Harvard Kennedy School recently announced[22] a scholarship program for graduate students to foster careers in government service, but Harvard College is funneling an even higher percentage of undergraduates into a few highly lucrative careers than it did a decade ago and has put no systems in place to steer students into public service—or even just a broader range of careers.

Looking beyond economic inequality, another effect of career funneling is to exacerbate the urban-rural divide. A 2022 study[23] by researchers from the US Census Bureau and Harvard found that, at age 35, nearly half of adults lived within 10 miles of where they lived at age 16 and roughly three-quarters lived within 100 miles. But higher education alters the equation: At 35, people with a bachelor’s or post-graduate degree live almost twice as far from their teenage home, on average, as those who didn’t complete college. An analysis[24] by the Wall Street Journal found that a quarter of all Ivy League grads gravitated to cities like New York, San Francisco, and Washington. More than 84 percent[25] of Harvard grads live in a major metropolitan area.

These statistics suggest that few students from impoverished rural communities who thread the needle and make it into the Ivy Leagues will return to live in those communities. “Universities want to have representation from Idaho and from West Virginia and so forth. But are they really trying to create thought leaders for those places?” Binder said. “My guess is that when universities think about attracting heterogeneous classes, they’re less concerned about what the kids are going to do with the rest of their lives than they are about attracting diverse classes in the first place—for their own bragging rights.”

Another reason to care about the career funnel is that our first jobs shape us. One of the ways elite firms market themselves to elite students is as vehicle to preserve their future options. Rivera found that employment in the industries she studied—particularly management consulting—was framed not as a mere job, but rather an “unparalleled learning opportunity” and a chance to “continue your education.” Davis describes the dynamic as offering them “a way of kicking the ball down the field while maintaining status.”

That’s another myth. Just as universities serve as “socializing agents,” Binder told me, so too is a young person’s first job, where they absorb the “norms and habits of the workplace,” with lasting effects. “Those years are more than additive,” she said, but rather “multiplicative, exponential—whatever. Between 22 and, say, 30 are really important. You’re thinking about what you want out of your life.”

Drawing young graduates into public service has myriad benefits. Economists Will Dobbie and Roland G. Fryer Jr. found[26] that serving in Teach for America after college improved young people’s racial tolerance, made individuals more optimistic about the life prospects of children from working-class families, and increased by 48 percent the likelihood that those graduates would work in education.

While an initial do-gooder experience profoundly affects attitudes and career choices, Yavaş argues that a first job in finance or consulting can lock someone into those careers even more strongly. It’s difficult for young people to break free of their golden handcuffs and jump off the high-status hamster wheel “even if they hate their jobs,” Yavaş said. “If they don’t feel like they have a safety net, they put up with alienation.”

Harvard’s assistant dean of civic engagement and service, Travis Lovett, grew up in a rural Virginia town with “more cows than people and one blinking traffic light.” His dad was a mechanic; his mom worked in a grocery store. He got into the University of Virginia, but attending would have left him $40,000 in debt, so he accepted a full scholarship at James Madison University instead. After a post-graduate stint in journalism, he landed at the Phillips Brooks House Association, Harvard’s largest public service organization.

Nowadays, Lovett told me, he especially enjoys speaking with fellow first-generation college students, who worry about being able to fit in. “I was the kid who didn’t know what spoon to use,” he explained. And although he enjoys his work overseeing Harvard’s community engagement efforts, he would like it to have more impact. The Crimson’s 2025 survey[27] found that less than 4 percent of seniors who’d landed a job would be doing public service or nonprofit work.

I asked Lovett what steps he would take to change the balance of career outcomes if he had $500 million—less than 1 percent of the endowment—to work with. First, he said, he would offer students an expanded range of possibilities, including “a public service internship for everyone who wants it.”

Last year, Harvard, which had 6,980 undergraduate students, subsidized 627 full-time summer public service internships. Lovett hopes to increase that by 50 percent over the next decade to meet student demand and the needs of low-income students who can’t afford to work for free. (Harvard, like many elite colleges, does not offer school credit for internships.) “I think there’s something really important about validating civic work early on,” he said, because while freshmen may be naïve, “by month two, they know what management consulting and investment banking is.”

Nearly everyone I interviewed believed colleges could do vastly more to help students think about how to live a meaningful life.

A broader solution might involve curbing the temptation of high salaries—what Rivera calls “the baller lifestyle” offered by investment banks and management consultancies—and reining in the strong, early signals many colleges send to their students that these are the careers most worth pursuing. Binder and Davis call financial temptations the “pull” and institutional status signaling the “push.” Colleges have the means to dial back both, Davis told me. “They can reduce some of the pressure.”

Reducing the pull, Lovett said, would require rebalancing the economic incentives. “At Google, they’re going to make $25, $30K for the summer,” he noted. “Meanwhile, we’re offering a $7,000 stipend to go work for the ACLU.” We need to “subsidize people to take career paths they otherwise wouldn’t,” Binder added.

Loan forgiveness is another route. Many graduate schools offer it for lawyers[28], doctors[29], and other professionals who enter public service. So does the federal government, though President Donald Trump recently issued an executive order[30] excluding students who work for organizations that, among other things, “aid or abet violations” of immigration law.

Most Ivy Plus universities already have committed to making college tuition-free for students from middle- and low-income families. Harvard students from families making $100,000 or less per year now get a full ride[31], complete with room and board, while those from families earning $200,000 or less enjoy free tuition. Most graduates, Lovett said, “walk away with less than $10K in debt.” Neither Harvard nor any of its competitors has yet backed away from such commitments in the face of Trump’s attacks.

But a paradoxical side effect of this generosity is that the colleges have surrendered debt forgiveness as a lever to coax students into public service. Consequently, Lovett favors direct subsidies or support for graduate work as an enticement for students “who’ve shown they’re really committed to this work” and to remove financial barriers that might stand in their way. Changing career outcomes might require the nation’s wealthiest institutions to invest in subsidizing public service. Only Harvard and its peer institutions could afford to do so, yet they’re the schools shaping the elite—and where the career funnel is the strongest.

Teach for America founder Wendy Kopp, who now runs its international sister program Teach for All, recently convened a working group to study how colleges might encourage young people to pursue virtuous and fulfilling careers. “By and large, universities do very little to foster intentionality about where students are going to put their most valuable resource, which is their time and energy,” she said.

More than 70 percent of the roughly 100,000 alumni of Teach for America and Teach for All end up doing mission-related work, she told me. Many are in education and government or launch nonprofits and advocacy organizations, Kopp said, “and most of them come in completely unsuspecting, thinking the training program is just two years.”

Nearly everyone I interviewed for this story believed colleges could do vastly more to encourage students to think about how to live a meaningful life. “They’re not being forced to ask hard questions about themselves,” Davis said. In a 2017 essay[32] for the Crimson, Mihir Desai, a professor at Harvard’s business and law schools, argued that the keep-your-options-open mentality of prestigious employment relieves students of the risk-taking they need to achieve alpha—“macho finance shorthand for an exemplary life.”

In an environment where only a few careers are deemed adequately prestigious, students’ ambitions may be more about maintaining status than pursuing something worthwhile.

A few educators stand out. At Stanford, professor Bill Burnett’s course[33] and lab[34] “Designing Your Life” teaches students design concepts and techniques to help them navigate life after graduation. The University of Notre Dame offers an introductory course[35] that asks students to consider how they can address the problem of poverty, personally and professionally. Yale’s most popular undergraduate course, now free to the public, is Laurie Santos’ “The Science of Well-Being”—an exploration of psychological research on how to live a happier, more fulfilling life. At Amherst College, a group of students[36] has pushed the school to offer more service-oriented and community-based learning. But collegewide curricular efforts on how to build a meaningful life are almost nonexistent.

One notable exception is the Center for Purposeful Work at Bates College, launched in 2017 and framed around principles of developmental psychology. The center’s work is predicated on a simple premise: “If you’ve got wellbeing in your career,” explained director Allen Delong, “you are twice as likely to have wellbeing in all the other areas of your life.”

Reflection on how to live meaningfully suffuses the Bates curriculum. The vast majority of students take at least one regular course on the concepts of work and purpose. The center offers classes on “life architecture,” design thinking (focusing on emerging adulthood psychology, life skills, and career development skills), and a series of courses led by professionals in fields from health care to journalism and music. Bates also subsidizes some 600 internships each year—about as many as Harvard, though its endowment is less than 1 percent as large. The school’s intentionality is reflected in some noteworthy outcomes. Bates reported, for instance, that 15 percent of its 2023 graduates went into education (five times the rate of Harvard grads), 16 percent entered the health field (more than twice the rate of Harvard grads), and 5 percent joined nonprofits. All told, only 22 percent of Bates graduates went into finance, consulting, and tech—well under half of Harvard’s combined rate.

To be fair, some students may choose Bates because of its strong record of producing public servants. And recruiters focus less on such schools, which, though well-respected, lack the Ivy League credentials their firms covet. But the Bates curriculum at least refutes the premise that colleges should remain on the sidelines. “I’ve often heard universities profess neutrality as it relates to people’s career choices,” Kopp told me. “I would say they’re really not neutral at all. They’re funneling students into financial careers.”

Instead, she said, we should be working to produce graduates “who are really putting their energy against the biggest challenges we face.”

Portela quit McKinsey in July. He’d received high ratings in his annual review, he told me, but really, the only thing tethering him to a career he didn’t love—and of whose social benefits he is skeptical—was money. The status, he can take or leave. “I don’t have anything to live up to,” he told me. “I don’t have to surpass my parents. I don’t have to meet any expectations.”

His explanation suggests why students from wealthy families are so susceptible to funneling; young people are often burdened with heavy family and social expectations and fear of failure. Steeped in an environment that considers only a handful of careers adequately prestigious, their ambitions may be more about maintaining status than pursuing something meaningful.

At least part of the reason Portela was able to break free, he and DiMichele both told me, was the service-oriented institution that shaped his formative years. Regis produces investment bankers and management consultants at far lower rates, DiMichele said, than the elite colleges to which it sends its students—and Regis alums who enter high-status professions tend to gravitate toward public interest work: “We produce more US attorneys than corporate lawyers.” He cites, for example, Kevin Driscoll, the former deputy assistant attorney general at the Department of Justice, who resigned after his unit was ordered to dismiss corruption charges against New York City Mayor Eric Adams.

Portela points to a pair of Regis programs focused on poverty that left a lasting impression. During a “freshman retreat,” students sleep over at the school and talk about service. At dinner, they are given slips of paper randomly assigning them a percentile ranking in global income and are fed accordingly. The bottom 70 percent receive a bowl of rice; the top 10 percent sit on a stage and enjoy a steak dinner.

During the school’s “urban challenge,” students travel to Camden, New Jersey, where they perform public service tasks like working in a soup kitchen. More importantly, they briefly simulate living in poverty: “They give you something like three dollars for the day and you have to feed yourself,” Portela recalled. That exercise, he said, can be transformative—even for kids of modest means. “I think there’s something noble about taking a bunch of middle- and lower-class kids and saying, ‘There are rungs beneath you on the ladder.’”

Regis, like Bates, has something to teach elite colleges about how curriculum can be used to shape values and access. “I think the kids who get off the merry-go-round are kids who suspect that the sheer repetition is going to drive them crazy,” DiMichele said.

Colleges that manage to build a socioeconomically diverse student body and teach them the importance of service are more likely to graduate young adults with a sense for life’s deeper purpose and truths, DiMichele said, and “quite frankly, there’s a hell of a lot more interesting things to do than put pitch books together for investment banks.”

References

- ^ Sign up for the free Mother Jones Daily. (www.motherjones.com)

- ^ survey (features.thecrimson.com)

- ^ estimated (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ sometimes emphasized (www.dailyprincetonian.com)

- ^ article (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ paper (sociology.ucsd.edu)

- ^ article (journals.sagepub.com)

- ^ Class Action (www.joinclassaction.us)

- ^ symbolic systems (symsys.stanford.edu)

- ^ Ivy Plus (blog.collegevine.com)

- ^ report (www.emerald.com)

- ^ 38 colleges (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ reports (hbr.org)

- ^ published (journals.sagepub.com)

- ^ reported (www.vox.com)

- ^ said (podcasts.apple.com)

- ^ Pedigree: How Elite Students Get Elite Jobs (press.princeton.edu)

- ^ surveys (features.thecrimson.com)

- ^ $53.2 billion (www.hmc.harvard.edu)

- ^ exceeds (perfectunion.us)

- ^ per student (www.collegeraptor.com)

- ^ announced (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ 2022 study (www2.census.gov)

- ^ analysis (www.wsj.com)

- ^ 84 percent (manhattan.institute)

- ^ found (www.nber.org)

- ^ survey (features.thecrimson.com)

- ^ lawyers (www.americanbar.org)

- ^ doctors (bhw.hrsa.gov)

- ^ executive order (www.whitehouse.gov)

- ^ get a full ride (news.harvard.edu)

- ^ essay (www.thecrimson.com)

- ^ course (www.youtube.com)

- ^ lab (lifedesignlab.stanford.edu)

- ^ course (socialconcerns.nd.edu)

- ^ students (careers.amherst.edu)