Jon Wiener: From The Nation magazine, this is Start Making Sense. I’m Jon Wiener. Later in the show: Trump seems to pose a unique danger to democracy, but historian Eric Foner explains that history shows many earlier threats to “our fragile freedoms.” That’s the title of his new book of essays. But first: Bill McKibben is suddenly hopeful about our chances for slowing climate change. he’ll explain why – in a minute.

[BREAK]

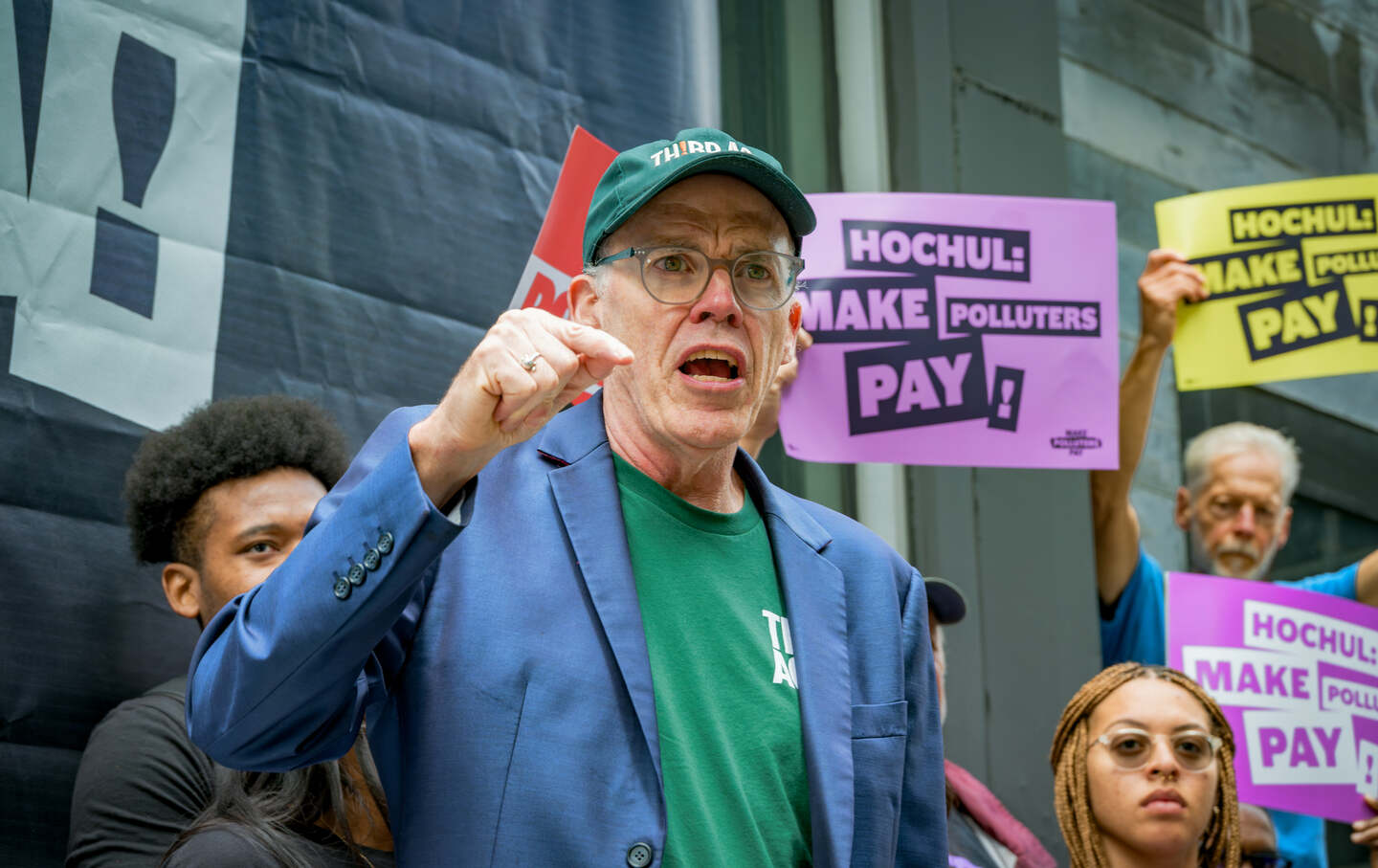

Now it’s time for some good news – really good news – from Bill McKibben, the climate writer and activist. He’s the founder of Third Act, which organizes people over 60 for action on climate injustice.

Bill’s 1989 book The End of Nature was the first book for a general audience about climate change. It’s been published now in 24 languages. He’s gone on to write 20 more books, and his work appears regularly in places ranging from The New Yorker to Rolling Stone to The Nation.

And of course, Bill helped found 350.org, the first global grassroots climate campaign, which has organized protests on every continent, including Antarctica, for climate action. Thanks to 350.org and its allies, the movement to divest from fossil fuels has become the biggest anti-corporate campaign in history, with endowments worth more than $40 trillion stepping back from oil, gas, and coal. We reached them today at home in the mountains of Vermont. Bill, welcome back.

Bill McKibben: Well, very good to be with you.

JW: You’ve devoted a lot of your life to telling us the bad news, and to leading the fight to make things better. But pretty much everything you said was going to happen is happening: the heat waves are hotter, the storms are bigger, the ice is melting, the temperature is rising. And Trump is doing his best to make all of that worse, to burn more fossil fuel – “drill, baby drill.”

But now you have some good news, really good news. At a time when almost everything seems to be going wrong, you see one thing that is suddenly going right, a really big thing. It’s the title of your book: Here Comes the Sun. Please explain.

BM: It’s just as disorienting for me as it is for anybody. Look, there’s never been a darker moment in my lifetime, not on the planet, where the heat is unrelenting and causing, as you say, exactly the kind of crises we knew it would. Not in our country, where, well, where democracy is flickering and faltering.

In the middle of all that there is one big, good thing suddenly happening that people haven’t really understood and that may be big enough that it actually has some impact on both those crises, the one of climate and the one of authoritarianism: and that’s the sudden finally surge in renewable energy. We’ve spent my entire lifetime talking about alternative energy from the sun and wind and kind of waiting for it to come around. It’s always been this sort of on-the-fringes alternative. But as of about three years ago, it’s not alternative anymore. The last 36 months have seen an almost unbelievable spike in the amount of solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries on this planet. And those three things are beginning to reshape our energy system in ways that are fascinating and potentially liberating.

The US is the one country not happily participating in this bonanza. Even the Saudis are installing vast quantities of solar panels at the moment, but around the world and in parts of our country, we’re seeing astonishing, astonishing change all of a sudden.

JW: One of the most striking things that you talk about in your new book Here Comes the Sun, is how one of the biggest problems in all of our past history is the geography of resources in the world that depends on fossil fuels: a few countries have a lot of oil and gas. They became the richest and the most powerful, and they dominate everybody else. But the sun shines everywhere. And the economic and political implications of that are incredibly significant.

BM: That’s absolutely right. You know that Trump has been talking about energy dominance since day one, and his idea is he has his foot on the neck of the world because we export more oil and gas than anybody else, so they’ll have to listen to us and on and on, but that’s not what’s happening now.

China has installed so much solar power. In May of this year, which is the last month for which we have good data, China was installing three gigawatts of solar panels a day, a gigawatt’s the rough equivalent of a large coal-fired power plant, so they were putting up a solar coal-fired power plant every eight hours. It’s happening so fast and spreading now to Asia and Africa with real speed and with it comes the absolute possibility for a kind of liberation. Look, Africa’s probably going to end up buying, at least for the moment, it’s solar panels from China or India.

But that’s different from buying oil because you buy a solar panel once and then you set it up and then the sun delivers the energy for free for the next 25, 30 years. That’s a very different proposition than being dependent on any country, much less. One is fickle and erratic as the United States at this point for your energy supplies going forward.

It’s not just by the way that these energy sources are concentrated in particular countries, it’s that in those countries, a few particular people end up usually controlling them. So not everybody knows, for instance, that in America, our biggest oil and gas barons for the last quarter century have been the Koch brothers. They control more refining and pipeline capacity than anyone else, and as you know, they used their winnings to erode the foundations of our democracy.

If anybody has any questions about why it was so easy for Donald Trump to kick them over, it’s because those guys had been at work for a generation. Making it happen in Russia, it’s Vladimir Putin, biggest oil and gas baron, using his winnings to launch a land war in Europe in the 21st century.

So the idea of a world that runs on a resource available to everyone, everywhere, that can’t be hoarded, that can’t be held in reserve, as you know better than most because you’ve been writing and talking about it your whole life, humans are very good at starting wars, but it’s going to take some doing to figure out how to fight a war over sunshine.

JW: The sun shines everywhere, but batteries have to be built and materials that go into batteries are not everywhere, and we need lots of really big rechargeable batteries. And if you read about this, there’s lots of naysayers who will say that mining lithium is disastrous for the environment, it causes significant water and air pollution. So although the sun may shine everywhere, the materials that go into batteries have been a problem. But you have good news on that front too.

BM: Sure. I mean, first of all, let’s be clear that you have to compare things with other things. That is to say, there is no free lunch anywhere, but there are more expensive lunches and less expensive lunches, and this is a lot less expensive. Yes, we should mine lithium as humanely and environmentally soundly as we can, and there have been at least the beginnings of some efforts along that – also cobalt, also copper. But the amount of these minerals that we need is relatively small in comparison with the amount that we’re mining now. And if you think about it even for a minute, you quickly realize why you go mine some lithium, you put it in a battery and there it sits for 25 years doing its thing. When the battery finally degrades, we now have the capacity to recycle that lithium and it’s valuable enough that we do, and then you just pull it out and start over with the next battery.

If you go mine some coal, what do you do? You set it on fire and then you have to go mine some more tomorrow. So the Rocky Mountain Institute estimated last fall that all the minerals for the battery transition through 2050 would be less in volume than the coal we mined last year on this planet.

Remember too, that when we’re thinking about as we always should be, human rights, human health, human suffering, let’s just lay aside climate change for a moment because that’s going to do more damage to human beings than anything that’s ever happened. But just in the right now, immediate moment, 9 million people a year die on this planet from breathing the combustion byproducts of fossil fuel. That’s one death in five. There’s 5 million children in Delhi. Two and a half million of them have irreversible lung damage just from breathing the air. That’s not necessary anymore. We can really begin to change that and actually within the last six months, we’ve started to see Delhi and much of urban India quickly adapting electric rickshaws to replace the two-stroke gas engines that have been fouling the air there forever. So it goes from that scale up to the example in this country. The two examples in this country that are fascinating are first California where there’s not that Governor Newsom has done everything right, but California over the last five or 10 years has built up enough momentum in putting up solar panels that they crossed some kind of tipping point this past year. Every day now, California generates more than a hundred percent of electricity it uses from renewable sources for long periods of the day. That means that at night when the sun goes down, the biggest source of supply on the grid is batteries that have been soaking up excess sunshine all afternoon.

The bottom line, California fourth largest economy on planet Earth uses 40% less natural gas to produce electricity than they did two years ago. That’s the kind of number applied all around the world that starts shaving tenths of a degree off how hot the planet eventually gets.

Do you know who’s putting up solar panels faster than California right now? The lone star state of Texas! And it’s not from any desire to save the climate, it’s sheer economics that are driving it.

The Trump administration is doing everything it can to get in the way of this change. They’ve all but banned new solar and wind. In fact, last week they shut down work on an 80% completed wind farm off the coast of Rhode Island, which if they have their way will stand as a kind of Stonehenge like ruin for generations just marking not our wisdom like Stonehenge, but our folly.

JW: And let me just say, Trump’s bizarre obsession with wind power is not based really even on the Koch brothers around politics, it’s an old personal thing but tell that story.

BM: It has something to do with his golf course in Scotland and he doesn’t want to look at, but truthfully, he’d be doing this anyway. You remember he told the fossil fuel industry last year when he was running for president, in a kind of Austin Powers moment, he was like, ‘give me a billion dollars and you can do anything you want.’ They gave him about half a billion, and that was apparently plenty.

But we’re going to do our best to stand up to Trump on all of this. Really, there’s three issues; aside from the underlying racism of the administration. It’s tariffs, deportation, and the attack on renewable energy. That seemed to be the kind of three-legged stool of policy, if you can call it that in this administration.

JW: The solar revolution means we have to change a lot of things, because solar power makes electricity, and a lot of our houses now have gas furnaces, gas stoves, gas dryers.

BM: Yep. If solar panels, wind turbines and batteries are the holy trinity for production of energy, let this Methodist Sunday school teacher tell you that the Holy trinity for its consumption are electric vehicles of all kinds, including E-bikes, which are pretty amazing, heat pumps replacing furnaces, and induction cooktops, which you can get for 60 bucks on Amazon if you are inclined to do Amazon stuff. Replacing the open campfire in your kitchen. These are all better than the thing that they replace. They are cheaper to run, have fewer moving parts, produce way less pollution. If you like going fast in cars, you can go way faster in an EV than you can in whatever you’re driving now.

JW: And I know that while you like electric cars, you love electric bicycles. Why is that?

BM: E-bikes. E-bikes I think may turn out to be the most interesting innovation of all. Look, a bicycle was good technology to begin with, and now we’ve essentially invented a bicycle with no hills, and it runs, it takes about a fifth of a cent to buy the electricity to take it a mile. That’s about what people are paying. It’s so elegant, it’s almost unbelievable.

So these are things that we can do. The trouble is we have to do them fast. We cannot sit around and wait for the market to do its thing because climate change. It’s happening in real time. The intergovernmental panel in climate change told us a few years ago that if we wanted to get back on anything like that Paris timetable, we needed to cut emissions in half by 2030, which by my watch is four years, and now as of today, four months away, that doesn’t leave us a hell of a lot of time, especially with Trump in the way. So we’ve got tons of work to do here and around the globe.

JW: And of course the oil and gas companies are fighting this with everything they’ve got. I find that a little puzzling because couldn’t they make a lot of money in solar?

BM: They can make a lot of money, but not as much money. And that’s the problem. There’ll be people who become millionaires and probably billionaires putting up solar panels and wind turbines, but once it’s up, you don’t need to buy more energy. John D. Rockefeller realized early on that if he could control the supply of this thing, then he was in the catbird seat like nobody before him, and that’s been the model ever since. Exxon makes you write them on another check every time you want some more energy. The sun does not. And for Exxon’s purposes, the sun delivering energy for free is the stupidest business model of all time. But for everybody else, it’s the best possible model, especially for poorer people and poorer countries. When you think about countries around the world, when you hear about countries around the world that are in debt crisis that are having to restructure, that are having austerity imposed on them by the IMF almost always the biggest item in their budgetary shortfall is paying for the next load of oil from the tanker that won’t unload it until they’ve got cash on the barrelhead. So this is liberation in so many ways.

JW: One of the lines in your book that I underlined more than once was “solar and wind are almost too cheap for our economy.”

BM: It’s hard to make the kind of profit that incentivizes companies to go put them up. That’s probably why China is leading the way right now, and it’s why it made extraordinary sense for the Biden administration to be trying to incentivize the kind of first round of this infrastructure buildup because yeah, that’s the problem, you got to pay to get it up in the first place, but once you do, the benefits to everything are so enormous and then they just go on forever. So think about where China’s going to be in a few years in comparison to say us. They’re going to be doing everything they do, manufacturing, especially with way cheaper energy than we are, and that’s going to give them a comparative advantage forever. Look, it’s not the thing that worries me the most. Climate change worries me the most, but it is kind of galling to see the Trump administration handing over the technological future to China.

This stuff was invented here. I mean, the solar cell comes from Edison, New Jersey. I mean there’s people out there – it was invented in 1954, which means there’s one or two people in your audience, my third act cohorts who are old enough to have helped pay for the development of solar cells by dropping dimes in payphones in the 1940s.

The fact that we’re just handing it all to China, it’s not that they’re eating our lunch. We’ve sent a crew of waiters in red caps over to Beijing to serve our lunch up for them and it should be kind of appalling to everyone.

JW: Well, I have friends who say that here in the consumption capital of the world isn’t the real solution for us to live more modestly and reduce consumption. So don’t get two giant SUVs. Get an e-bike. Don’t live in a big house. Live more simply, avoid air travel, don’t eat meat. Wouldn’t we all be better off if we all did these things?

BM: I’ve got no argument with it and you’re sort of describing my life in Vermont, but a, it’s not going to happen fast enough to catch us up with climate change. A hundred million human beings enter the consuming class every year now mostly in Asia. And the idea that they’re simply going to be persuaded to not to follow what’s happened from so many cases here seems unlikely to me. And two, we kind of had an experiment about this five years ago. You’ll remember, I’m afraid, the first couple of months of the COVID crisis, we changed our lives more than any environmentalist would ever have imagined making anyone change their life. Nobody flew, nobody drove, nobody did anything for weeks. We just sat at home and stared at the wall. It turns out that emissions dropped, but by a lot less than you’d expect. They were down about 10% at the height, which means I think that the problem is less with individual choices and more with the machinery that runs this thing we’re currently calling civilization.

So a hundred years from now, will humans have figured out better ways to amuse themselves in ways that put way less stress on the planet? I bet. I think we’ll live very differently, and I’ve spent a lot of time writing about that deep economy in some ways my favorite book I ever wrote, and it’s very much on this subject, but do I think we’re going to do that in the next four years around the globe in numbers sufficient to alter the trajectory of carbon in the atmosphere? I don’t. So I think that we better figure out how to meet the desires that we currently have with the technology that won’t destroy the world and will destroy less of it in the process.

JW: Tell us about Sun Day.

BM: Sun Day is our effort to try and bring this to the US. It’s on September 21st, the Autumnal Equinox, and it’s going to be hundreds of events all across the country. You can find them at sunday.earth. That’s the website sunday.earth. It’s a very beautiful website because it’s going to be a very beautiful day. A lot of these will be solar-powered concerts and people building habitat for humanity homes with solar panels on the roof and groundbreakings at solar farms and on and on and on. There’ll also be some angry protests outside gas pipelines that we don’t need because we should be putting up solar and stuff.

It has two goals. One is to make it easier to do solar. Blue cities and blue states as well as red cities and red states can do a lot without the federal government to reduce the permitting load, it costs three times as much to put solar on your house in this country as it does in Australia or the EU. And that’s mostly because we have too much licensing, permitting all this. There are good easy app-based ways to get around that everybody else uses, and now we should too. Second purpose of Sunday, maybe the deepest is just to drive home this notion that it isn’t alternative energy anymore. The analogy I’ve been using, we’re used to thinking of this stuff as the Whole Foods of energy. It’s nice but pricey. But it’s the Costco of energy: It’s cheap; it’s available in bulk; it’s on the shelf ready to go. Let’s get to it.

JW: “Let’s get to it.” Starting with Sun Day on our calendar, September 21st, the Autumn Equinox, more info at sunday.earth. So everything is going wrong except this one big thing. In these dark days, there is one bright light: the sun. Bill McKibben’s new book is Here Comes the Sun: A Last Chance for the Climate and a Fresh Chance for Civilization. Bill, thank you for this wonderful book, thanks for everything you do, and thanks for talking with us today.

BM: Back at you, brother, a real pleasure. Take care.

[BREAK]

Jon Wiener: It often seems like Trump is posing a unique threat to our freedoms today. But historian Eric Foner says our present battles are not unprecedented. Americans have won rights, and lost them, at different points in our past. He’s called his new book, Our Fragile Freedoms. It’s a collection of essays, almost 60 of them. Of course, Eric taught American history at Columbia for several decades. He’s written many award-winning books on the Civil War and Reconstruction eras. His book on how Lincoln changed his mind about slavery and Black people – it’s called The Fiery Trial – won the Pulitzer Prize, the Bancroft Prize, and the Lincoln Prize. Eric’s written for The New York Times, The TLS, The LRB, and The Nation, where he’s a member of the editorial board. We reached him today at home in Manhattan. Eric, welcome back.

Eric Foner: Good to see you, Jon.

JW: Trump doesn’t read books, but he does seem to care about history, and right now he’s launched a campaign against the Smithsonian, where he says “Everything discussed is how horrible our country is, how bad slavery was. Nothing about success, nothing about brightness, nothing about the future.” But what could be brighter in our history than freeing the slaves? And if he’s interested in the future, how about those who fight for a future of greater equality?

EF: Yes, I think that’s a legitimate critique of the President’s view of history. It’s either all good or all bad. I mean, I think that most historians would say this is not a very good way of categorizing historical scholarship. Some of it will generate brightness, some will generate darkness, but most of history is a kind of mixed bag. There are many things to be proud of in American history, some of them you just mentioned a few minutes ago, and there are many things to be ashamed of, slavery, number one, Japanese internment during the Second World War.

One of my favorite quotations about the writing of history that I used to pass along to my students came from the philosopher Nietzsche, who basically said there were three kinds of history, three kinds of writing of history. One is what you’d call ‘antiquarianism,’ people searching for their roots and their relatives, et cetera. Nothing wrong with that. The second kind is what he called ‘monumental history.’ That’s what most history is actually, and it’s certainly what Trump wants. He wants to build an entire park full of statues of great Americans in Washington DC. It’s not exactly that it’s false, It just is rather limited and doesn’t give you a full picture of our history. And the third one is ‘critical history,’ said Neitzsche — critical history, “the history that judges and condemns.” So I think there are many more kinds of history than the current debate is allowing for.

JW: You write in your new book that your own education as a historian ‘began at home.’ Tell us about your father and about your uncles.

EF: Yes. My father, Jack Foner was also a historian, although he didn’t go to college planning to be a historian and neither did I. When I went to college, I wanted to be an astronomer. But in my home, it was on the sort of liberal left-wing part of the political spectrum in the suburbs of New York where I grew up. My parents were among the minority of white people who thought that racism, Jim Crow, was outrageous. It was a violation of the Constitution. And this was really something they devoted a lot of their time and energy to fighting against — the way racism was so pervasive in the 1930s, 1940s and fifties until the civil rights era. So yes, I learned about racism, and I learned about struggles against racism. Frederick Douglass was a great hero in my family. My uncle Philip Foner published five volumes of Frederick Douglass’s great writings and speeches, and my teacher in high school had never heard of Frederick Douglas, but in my home, Frederick Douglas was an important presence.

JW: And what about your uncles, Henry who became head of the Fur Workers Union and Mo, who was the head of the 1199 Hospital Workers Union?

EF: How could I forget them. All four of these gentlemen, my relatives, my father, and uncles, all four of them were blacklisted in the 1940s and ‘50s. They could not get teaching jobs because of their left-wing political views. So that was another thing I learned at home, and in a way, I was thinking of that when I wrote the title of this book, Our Fragile Freedoms, that I learned from observation of my parents and my uncles.

JW: Let’s get back to Trump here. When Trump does something terrible, like, I don’t know, sending ICE agents to grab undocumented residents off the streets of Democratic cities and taking them away to far away countries, people say ‘nothing like this has ever happened before.’ But in many cases, as you point out in your new book, especially like this one, it has happened before. In fact, worse has happened before. For example, ICE enforcement today has a lot in common with what happened under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

EF: Yes, the Fugitive Slave Act authorized the federal government to appoint new officials who could do what ICE does, just grab people off the streets, haul them to a judge who would then, it was really just a question of identification, not of whether the person was really a fugitive running away from slavery, but the Fugitive Slave Act also had a different effect, which was to galvanize abolitionist sentiment in the North. Many people who were not radical abolitionists before the 1850 found the fugitive slave law more than they could swallow and took to the streets to prevent the apprehension of people accused of being fugitive slaves. But the basic picture here of oppressed people running away, trying to get across a border in order to enjoy freedom and being apprehended by federal agents, that picture is here in our streets today.

JW: And one other interesting parallel, today we have these sanctuary laws that declare that cities and towns refuse to cooperate with ICE. How does today’s sanctuary movement compare with the resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850?

EF: There’s considerable similarity between communities that say, ‘our police or our judges will not cooperate with the apprehension and deportation of people accused of being illegal refugees’ You might almost say — the Supreme Court of Wisconsin declared the fugitive slave law unconstitutional. The Supreme Court of the United States overturned that judgment. So in other words, this battle over who’s entitled to freedom, who enforces the law or tries to enforce the law, those things have been a part of our history for quite a while.

JW: Another parallel, Trump thinks there’s too much about how bad slavery was in our textbooks, in our teaching, and he’d like to basically hide that history. You write in your new book, Our Fragile Freedoms, about a terrible chapter of American Black history that was hidden for a century and then recently rediscovered, and that’s what happened in Tulsa in 1921. We always were told it was a race riot, but it turns out it was a massacre, probably the deadliest instance of racial violence in the country’s history. And we’re just now learning more about what happened there and how that history was hidden. Remind us briefly what we now know about what happened in Tulsa in 1921. Tulsa at the time was an important place, the oil capital of America with a flourishing Black community.

EF: Yes, Tulsa was sometimes called the Black Wall Street because it had a thriving middle class. Most of the Black people living there, this is around 1920, 21, as you said, most of the Black people living there were not Wall Street people, Black or white, but were poor laborers working in the homes of white people or other kinds of menial jobs.

But the World War I era was one with many racial altercations in the United States, east St. Louis, Chicago, you name them, Tulsa was probably the most violent of them all. What it ended up with the entire neighborhood of Black Wall Street being burned to the ground, hundreds of people without a place to live. Another adage of historian is ‘history is what the present chooses to remember.’ The people of Tulsa, or that is to say, anyway, the white people of Tulsa, made a very concerted effort to hide, in a sense, what had come; to forget what had happened in the Tulsa race massacre of 1921.

JW: How did they manage to hide it? You’d think the killing over a hundred people, and the destruction of the houses of thousands of people, couldn’t be kept a secret.

EF: Scott Ellsworth, who wrote the book that I was reviewing in this case, he’s very clear about this. The police went around from photo studio to photo studio apprehending photographs that showed the destruction after the riot was over in Tulsa, teachers were told if they mentioned this in class, they would not keep their jobs. In other words, it was a concerted effort to avoid any discussion, and probably Black people were kind of frightened that if they started talking about it again, you might run into further violent problems.

JW: You’re probably known best for your work on Reconstruction after the Civil War in your book – The Second Founding is about the amendments to the constitution that were passed in the wake of the Civil War, 13th abolishing slavery, the 14th guaranteeing equal rights and establishing birthright citizenship. The 15th guaranteeing the vote to Black men. The 14th is the one that’s in the news these days because Trump for a long time has said he wants to abolish birthright citizenship, and on day one of his second term, he signed an executive order, abolishing birthright citizenship, which courts have ruled is unconstitutional. I notice it’s on its way to the Supreme Court, but thus far, Trump has not appealed the substance of the rulings that say the whole concept of abolishing birthright citizenship is unconstitutional. All he’s challenged is peripheral and the procedural issues. I wonder if this could be because even his flunkies and his Yes, men at the Justice Department are telling him that his case to abolish birthright citizenship is a sure loser at the Supreme Court because it’s definitely in the 14th amendment to the Constitution. You’re our expert on the 14th Amendment. Tell us how it was passed and why.

EF: This is the culmination of a long battle, which took up most of the first half of the 19th century. It’s in there because abolitionists and anti-slavery people of all kind led a campaign to create a situation where anybody born in the United States is a citizen of the United States automatically. They wanted to create what Frederick Douglass after the war called ‘a composite nation,’ a nation in which people of all backgrounds, of all races, religions, creeds, could cooperate with each other. And the first sentence of the 14th Amendment says, ‘any person born or naturalized in the United States is automatically a citizen.’

What will happen when the substance of this gets up to the Supreme Court? I am not a betting man, and I’m not going to throw my money away by betting on this. And I think one could certainly imagine scenarios in which the Supreme Court went along with Trump.

If you go by the text of the Constitution, which is what many conservatives think is the best way to interpret the Constitution, you’re going to have to end up with birthright citizenship being part of the constitutional system, something that the President can’t just abrogate with one executive order as he has tried to do.

The basic lesson here is that rights can never be taken for granted. You cannot assume that because rights have been gained that they can’t be lost also. There’s one lesson. It’s exactly as many people used to say in the 19th century, ‘the price of liberty is eternal vigilance,’ and where we’ll end up, we cannot say

JW: Eric Foner – his new book is Our Fragile Freedoms. It’s a collection of almost 60 essays. The Yale historian Elizabeth Hinton calls the book “a vital tool for navigating our present struggles for justice and equality.” Eric, thank you for all your work, and thanks for talking with us today.

EF: Thank you, Jon. Nice to be here.