PUBLISHED August 17, 2025

KARACHI:

To wait for a saviour is to inhabit a paradox — where passivity masks longing, and hope suspends time. This condition resists easy categorisation: it is neither purely mystical nor wholly political, neither naïve faith nor mere deferral. At its core lies a fundamental tension between the unbearable present and an imagined horizon — one that promises not just change, but transformation. This horizon may be divine or secular, collective or intimate, abstract or vividly embodied. The figure awaited may never arrive; yet the act of waiting continues to shape our dreams, define our silences, and haunt the thresholds of our becoming.

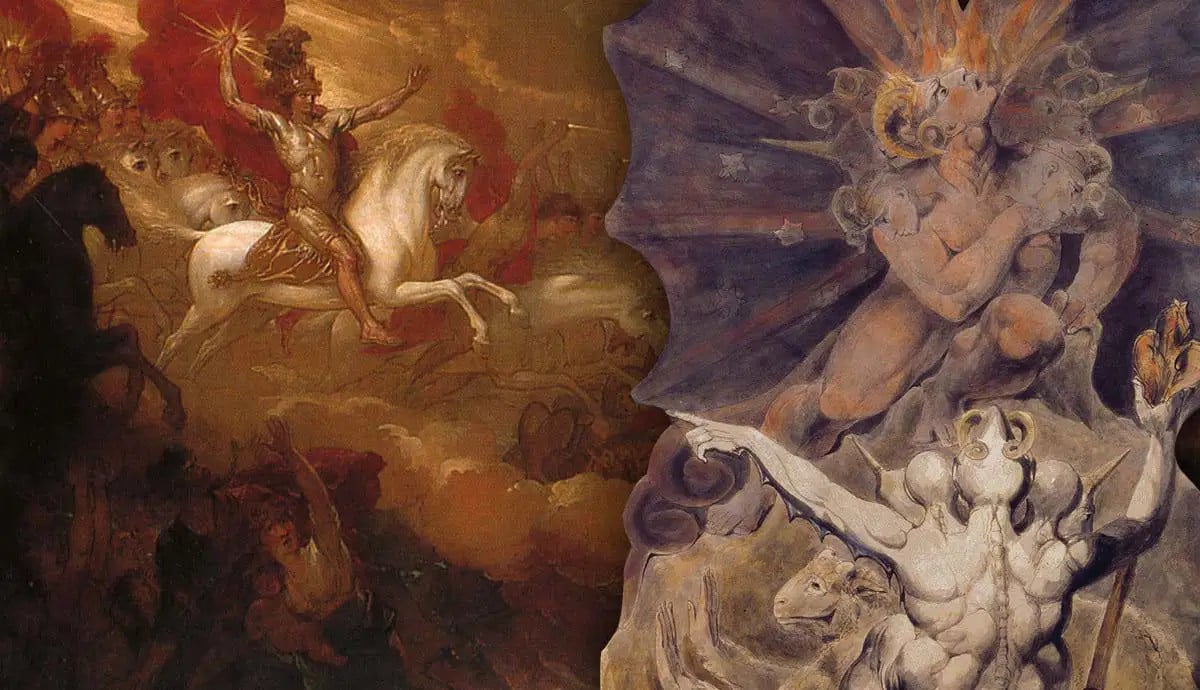

Walter Benjamin reminds us that “the Messiah comes not only as the redeemer, he comes as the subduer of Antichrist.” This duality — redeemer and destroyer — reveals the messianic figure as not just a bearer of peace, but a force of historical rupture. Benjamin further warns that even “the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins,” insisting that the task of hope is as much about redeeming the past as anticipating the future. Franz Kafka, with his paradoxical clarity, wrote: “The Messiah will come only when he is no longer necessary… on the very last day.” This deferral of arrival mirrors the way hope often remains just beyond reach. Yet Ernst Bloch distinguished between false hope that enervates and “concretely genuine hope” that fortifies the soul. And perhaps Che Guevara captured the ethical charge of such hope in its most radical form when he exhorted: “Be realistic, demand the impossible!”

Such waiting, then, is not a singular or static experience — it emerges from a web of human needs, histories, and narratives. Beneath its various forms lies a layered architecture of emotion, ideology, and belief. These dimensions may differ in their source or articulation, but they are all animated by the same inner ache: the yearning for another presence to enter the scene of absence, to alter the course of what seems unchangeable.

Psychological and existential need

Humans crave order, redemption, and meaning, especially in the face of suffering or chaos. Waiting for a saviour externalises hope — placing the burden of resolution onto another imagined presence. This impulse reflects a profound existential tension: the yearning to be rescued versus the terror of being ultimately alone and responsible for one’s salvation. The longing for an external saviour becomes a proxy for confronting internal fragmentation. It is not merely romanticism but an ontological hunger — a need deeply embedded in the very condition of being human.

Political and social function

Waiting for a redeemer often becomes a tool of ideology or control. It urges inaction in the face of injustice, whispering that change is always on the horizon but never in the moment. Political regimes and institutions have long exploited this impulse, urging citizens to wait for the revolution, the leader, the next election. The narrative of an impending saviour becomes a method of deferral — pushing justice, reform, or transformation into a nebulous future.

However, this same waiting can also mobilise resistance. The image of a coming change sustains hope, fortifies solidarity, and keeps oppressed communities enduring through pain. In some cases, the figure of the awaited one functions like a placeholder for collective will, anchoring revolutionary imagination. Thus, the messianic becomes double-edged: it can be opium that dulls or oxygen that sustains, depending on how it is interpreted and held.

Religious and mythic archetype

The awaited one emerges as a mythic constant across cultures and epochs. From Christ to the Mahdi, Maitreya to Kalki, traditions everywhere are haunted by the promise of a final redeemer. According to thinkers like Carl Jung and Mircea Eliade, such figures are not merely religious inventions but archetypes — expressions of the psyche’s deep longing for order, justice, and transcendence.

These messianic narratives are not passive fantasies. They are containers for moral and metaphysical longing — stories of balance restored, injustice defeated, harmony regained. In this sense, waiting becomes not inaction but ritualised hope. It is an embodied narrative structure, enacted in prayer, poetry, and political imagination alike.

Romanticism, yes — but in the Classical Sense

In the classical Romantic tradition, the act of waiting gains its own value. Romanticism privileged longing over fulfilment, the sublime over the rational, the journey over the destination. In this sense, waiting itself becomes meaningful — not merely as a means to an end, but as a state of heightened consciousness.

To wait is to be fully present in one’s yearning, to recognise the sacred in incompletion. The awaited one becomes less a solution and more a mirror, reflecting our deepest desires. Thus, the romanticism of the awaited figure is not naïve, but tragic-hopeful — a mode of enduring and meaning-making.

Modern critique

Modern philosophers and activists have mounted serious critiques of the saviour complex. Figures like Frantz Fanon, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Angela Davis have warned against waiting as a form of disempowerment. The mantra “we are the ones we’ve been waiting for” rejects the deferral of agency, insisting that change must emerge from the collective self, not an external redeemer.

Derrida’s concept of “the messianic without a messiah” captures this shift. It speaks to a radical openness toward the future — an ethical readiness to be transformed — without clinging to the image of a specific saviour. Here, the figure of the awaited one dissolves, but the impulse toward justice and change remains.

The Awaited One in literature

Literature has long been the hearth where mythic and philosophical flames burn together, where private longing and public history meet in the form of image, rhythm, and paradox. The figure of the awaited one — at once eschatological and existential — finds one of its most poignant and challenging expressions in the work of two poets: Forugh Farrokhzad and Jaun Elia. While earlier thinkers and poets such as Iqbal imagined the awaited one as a moral and spiritual imperative, Farrokhzad and Elia place the figure under the sharp lens of modern disillusionment, forging from their distinct poetics two radically divergent critiques of messianic hope.

In Farrokhzad’s poem “Someone Who Is Not Like Anyone” (kasi keh mesl-e hichkas nist), the awaited one is neither divine nor doctrinal. She frames her entire vision through the innocent but knowing eyes of a child. This child does not wait for a Mahdi or a Christ but for a figure of intimacy, dignity, and quiet transformation. The poem lists what this awaited one is not: he is not like the father, not like Yahya, not like the mother. In this series of negations, Farrokhzad destabilises traditional relational archetypes, refusing inherited roles.

Yet what emerges is not absence but potential — the awaited one, the poem insists, can do things no one else does. He can read hard words. He can subtract a thousand from twenty million. He can buy things on credit. He can distribute Pepsi and hospital numbers. These banal gestures shimmer with the poet’s genius: Farrokhzad displaces the messianic from the heavens to the street corner. The awaited one is neither supernatural nor victorious — he is the one who understands systems, who has access, who can navigate bureaucracies and basic needs.

The tone here is revolutionary in its restraint. There is no thunderclap of prophecy, no eschaton; instead, there is gentle insistence. Farrokhzad’s saviour is made from the materials of this world. The child’s imagination is not naïve — it is fiercely precise. Farrokhzad’s awaited one is, in essence, a dream of dignity reconstituted in the aftermath of social trauma. He is an ethical figure who has no miracle to perform other than restoring fractured dailiness. The poem, therefore, becomes a quiet theological coup: Farrokhzad trades metaphysics for material justice, but retains the sacred tone of longing.

Thus, Farrokhzad transforms absence into ethical imagination. Her awaited one may never arrive in a grand sense, but she dreams nonetheless — and through that dreaming, constructs a world worth saving. The tone is tender yet defiant, childlike yet visionary. She rejects messianic spectacle, but not the right to hope.

If Farrokhzad’s voice is the quiet reimagining of presence, Jaun Elia’s is the sardonic dirge for presence itself. In one of his most philosophically charged couplets, Elia writes:

Woh jo na āne wālā hai nā, us se mujh ko mat̤lab thā / Āne wāloṅ se kyā mat̤lab — āte haiṅ, āte hoṅge (That one who is not going to come — it was he that I cared about. / What do I have to do with those who come? They come; they will come.)

This line encapsulates Elia’s radical anti-messianism. The saviour is meaningful precisely because he is absent. The act of waiting becomes, in Elia’s hands, a psychological theatre of deferral — not because we believe in arrival, but because we need the illusion. The poet exposes a deep truth of the human condition: we attach value to what remains just out of reach. Arrival is banal; it closes the loop. Non-arrival sustains the myth, nourishes desire, and preserves the sublime distance between hope and its object.

Unlike Farrokhzad, whose tone holds pain and possibility in a kind of luminous suspension, Elia’s tone is irreverent, ironic, and often cruel. His awaited one is a spectre — conjured not from belief, but from absence. There is no tenderness, only razor-sharp scepticism. Where Farrokhzad seeks to repair the world through re-imagined hope, Elia seeks to unmask it — to show that our longing for salvation is often a refusal to face the emptiness of the present.

This is not to say that Elia lacks emotion — on the contrary, his poetry is saturated with loss, disillusionment, and intellectual despair. But he never gives this despair the crutch of transcendence. His awaited one never comes — and this non-arrival is not a disappointment, but a metaphysical condition. Elia’s messianic is an infinite postponement, a paradoxical affirmation of futility that becomes, strangely, a form of honesty.

Comparative reflection: two poetics of longing

Farrokhzad and Elia dramatise two radically different responses to the collapse of traditional messianic belief. Farrokhzad channels this collapse into a new ethics of presence — where waiting is infused with care, imagination, and earthly justice. She holds onto longing not as a weakness but as a radical act of reconstruction. Her awaited one is reconfigured through secular compassion.

Elia, by contrast, does not reconstruct; he demolishes. He does not offer an alternative saviour — he questions the very grammar of salvation. His tone is that of someone who has seen too much, who refuses to lie to himself. For Elia, the saviour matters only because he never arrives. His poetry is not about deferred redemption, but about the exposure of our dependence on deferral itself.

Together, these two voices — one Persian, one Urdu; one marked by hope, the other by irony — articulate the dialectic of modern waiting. Farrokhzad lifts the ruins of theology and builds small altars of kindness. Elia sets the ruins ablaze, revealing the absurd architecture of longing. Both, in their way, preserve the sacred tension between expectation and abandonment.

The Awaited as mirror

The awaited one, as seen through these poets, is not always a divine emissary. Sometimes he is a projection of our needs, a critique of those needs. Sometimes, he is a question we refuse to answer. In Farrokhzad’s poem, he is the soft silhouette of dignity glimpsed through the eyes of a war-scarred child. In Elia’s, he is the absent cypher of a longing that mocks itself even as it persists.

To wait, then, is not always to believe. It can be to imagine otherwise, to bear witness, to laugh, to resist. The awaited one becomes, in the end, not a saviour from without, but a mirror held up to our most persistent human condition: the hope that someone, somewhere, will make sense of it all.

And so, we wait — not for the end, but for the meaning forged in the act of waiting itself.

Aftab Husain is a Pakistan-born and Austria-based poet in Urdu and English. He teaches South Asian literature and culture at Vienna University

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the author